The Fed has made clear that it is struggling to balance the two parts of its dual mandate: inflation and employment, and now faces a third concern of political pressure. It is leaning toward employment risks over inflation risks right now, but will be constrained from aggressive moves while this tension persists, along with trying to preserve its policy independence amid heavy political interference.

Having cake and eating it too

The Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977 explicitly set the Fed’s policy goals, and actually named three: “promote the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.” The goal of moderate long-term interest rates is often left out, under the assumption that achieving the first two will naturally bring moderate interest rates. So the Fed has adopted its so-called “dual mandate” of maximum employment and price stability (i.e., low and stable inflation).

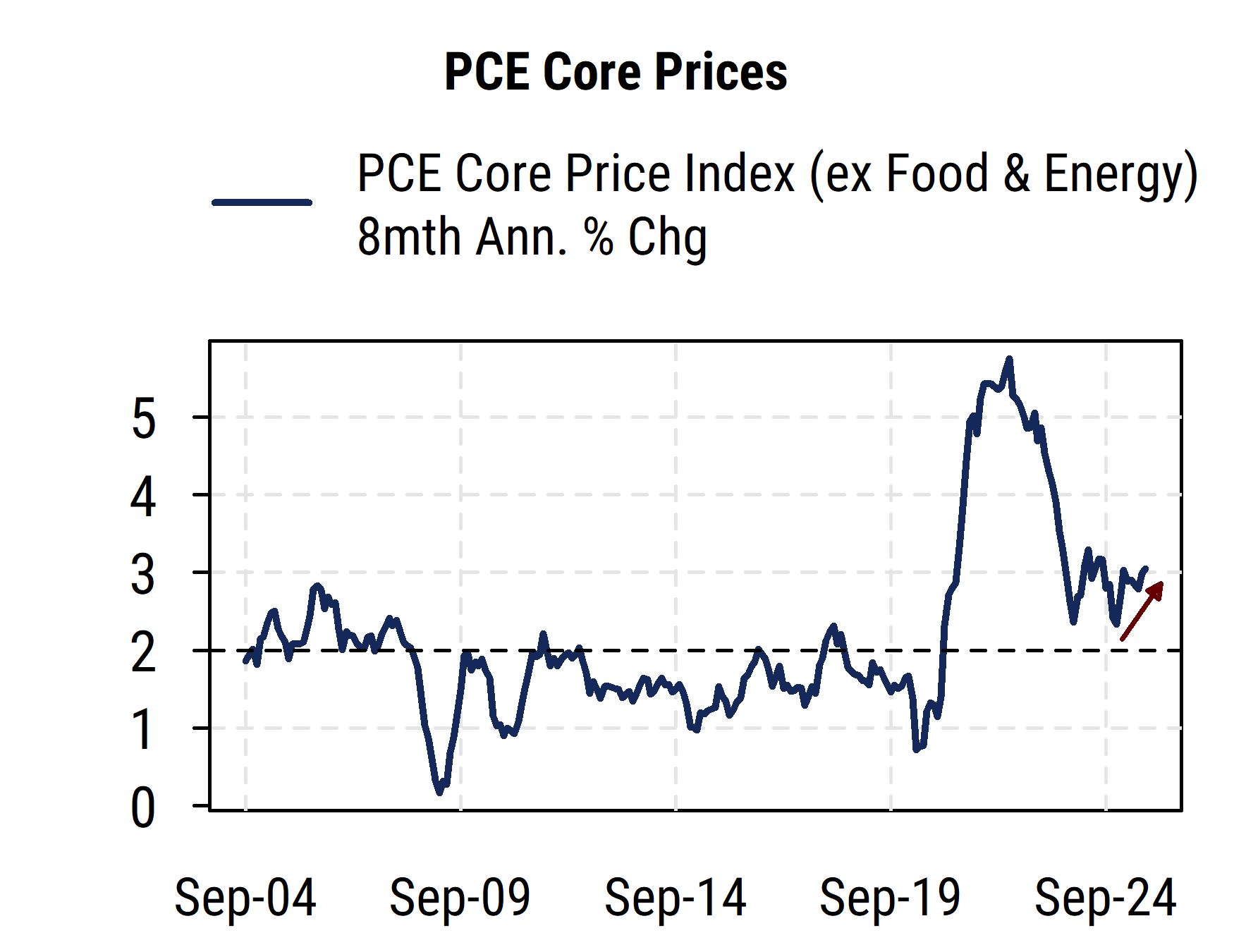

In more recent decades, the Fed’s target for “price stability” has been specified as being a longer-term average of around 2% for the core PCE price index (i.e., excluding volatile food and energy prices which are outside the Fed’s control and more volatile). There is not a specific definition of “maximum employment”, but it is assumed to mean the lowest possible unemployment rate consistent with stable inflation.

The usual assumption, based on the old Phillips Curve, is that inflation goes up if the economy is “too strong”, meaning too many people working (low unemployment) and spending money, and vice versa. This has not actually been the case for decades now, and the Fed has backed away from it somewhat more recently. But there is still a strong assumption that a weak labor market and the corresponding lower growth in consumer spending puts downward pressure on inflation, and vice versa. So the Fed’s mandate is to try to “have its cake and eat it too” by having full employment and low inflation at the same time. This is in fact possible and was arguably close to happening in 2024 (as it did in the late 1990s), but is tricky and depends on many factors other than monetary policy, which are now making it much more difficult.

We have long held that fiscal policy is much more important for the economy than monetary policy, but markets focus much more on monetary policy, particularly in the short run. In addition to good fiscal policy, productivity growth is the crucial factor for allowing full employment and low inflation to coexist. Unfortunately, productivity is the hardest factor to measure accurately, particularly in the shorter-term. So the Fed essentially has an impossible task: keep employment high and inflation low while only having the blunt instrument of short-term interest rates (and to some extent, bank regulation) to do it. The Fed has no real influence on fiscal policy or productivity growth, so it just hopes for good conditions from those factors to make its difficult job more manageable.

Losing on both sides of the bet

The problem right now is that the Fed sees clear signs that the labor market is weakening and also signs that inflation is both above its target and rising. So both parts of its dual mandate seem to be going the wrong way.

Much of the inflation pressure is attributable to tariffs and other policy actions made by the Trump administration this year, and thus does not reflect “excess demand” from consumers as would normally be assumed. Inflation was trending lower in 2023-24 and had almost reached the Fed’s target last year before progress was halted and reversed this year.

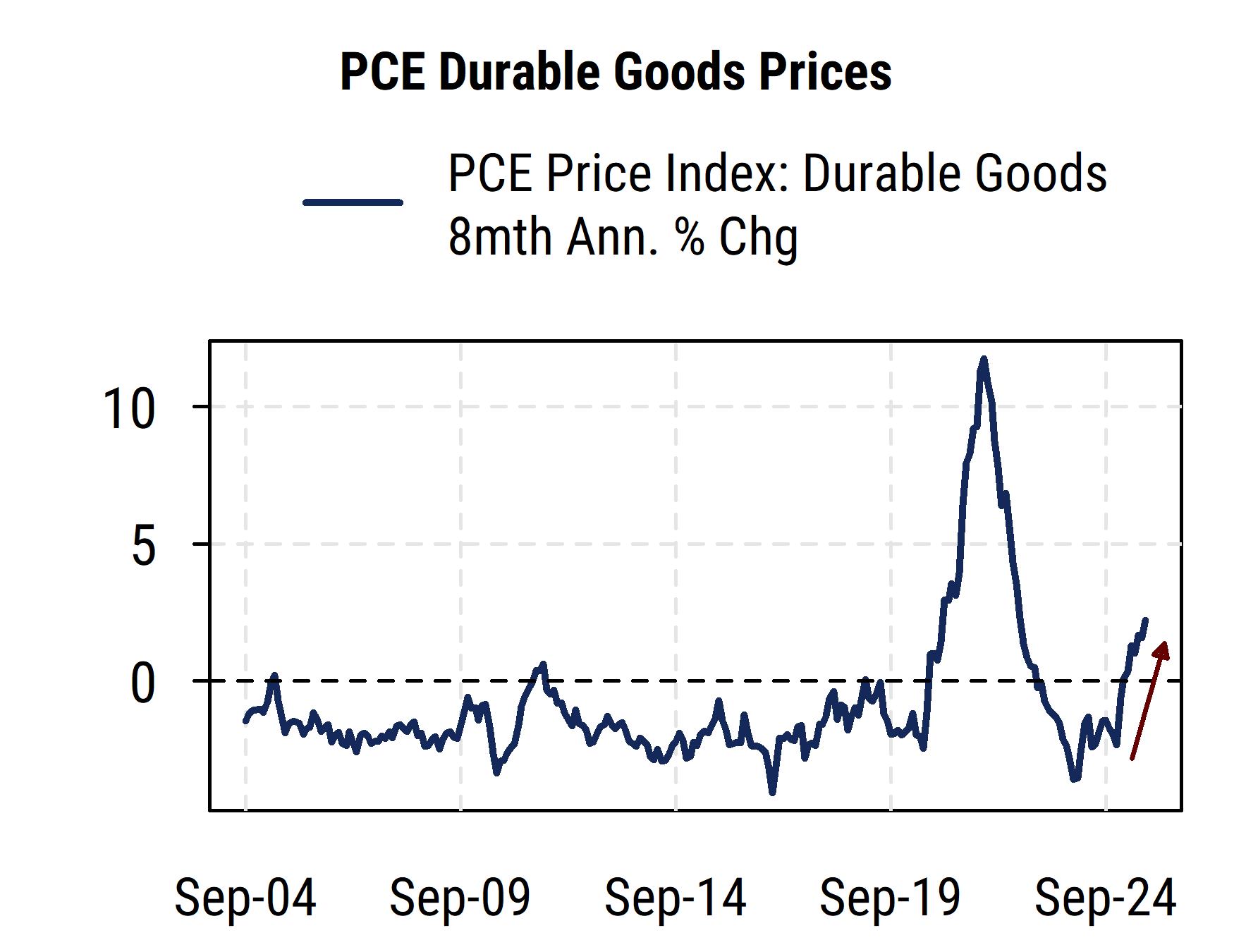

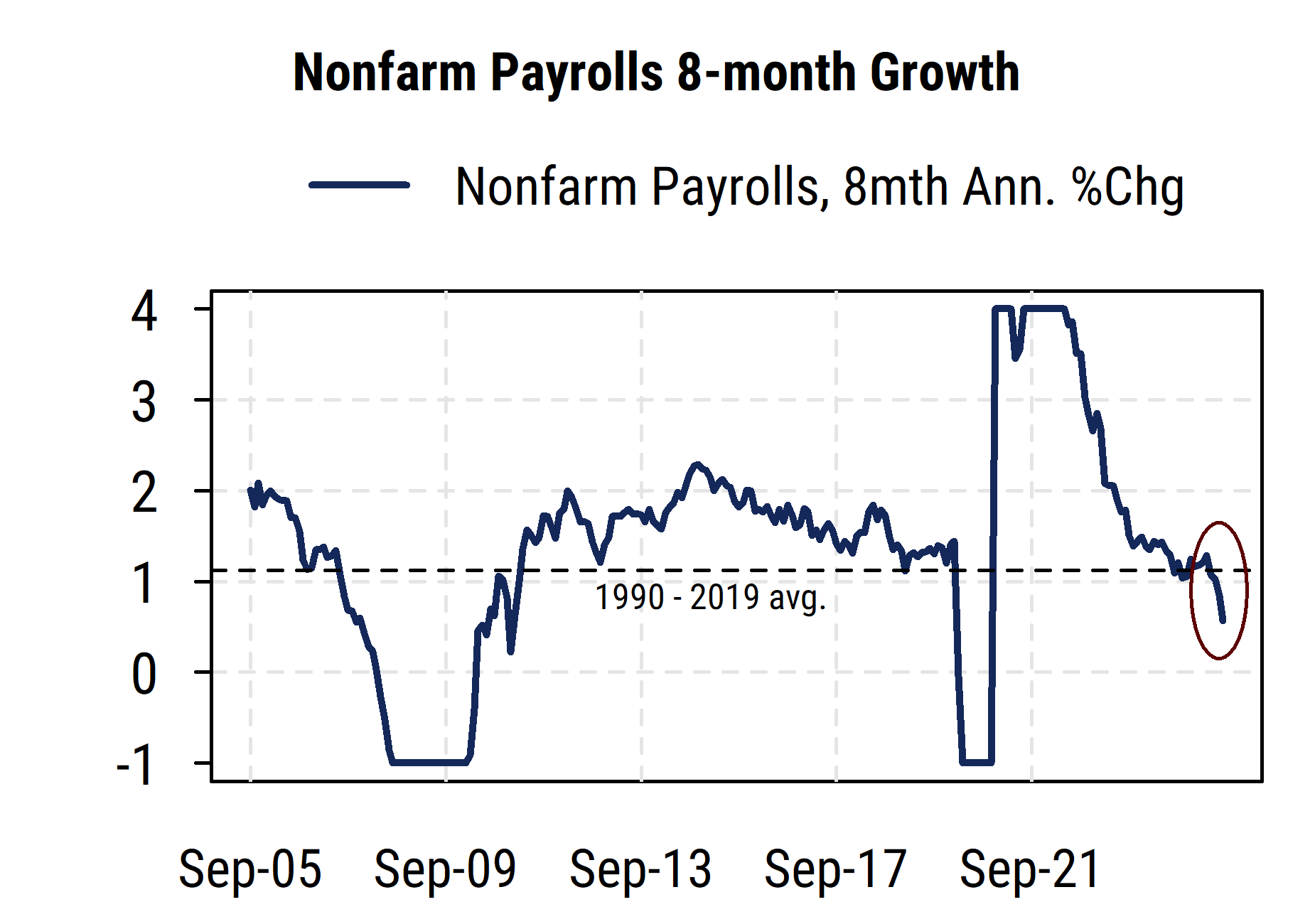

The charts below highlight the issue. We show 8-month annualized figures for several of them to capture the data available for the first eight months of this year under Trump policies.

Inflation based on the Fed’s preferred measure (core PCE price index) is notably above-target and rising over the first eight months of this year.

Source: Mill Street Research, Bureau of Economic Analysis

Durable goods (cars, appliances, furniture, etc.) are most affected by tariffs, and show clear inflation pressure. Under normal (non-COVID, non-tariff) conditions, durable goods prices tend to gradually decline, and had returned to doing so after the post-COVID jump. But this year inflation in durable goods has rapidly turned higher due to tariff pass-through.

Source: Mill Street Research, Bureau of Economic Analysis

While inflation is rising (or at best not falling) this year, employment growth is slowing due to both weaker demand and lower supply (immigration). The 8-month annualized growth rate of non-farm payrolls has slowed to just 0.56%, well below the pre-COVID long-run average and the lowest outside of COVID since early 2011.

Source: Mill Street Research, Bureau of Labor Statistics

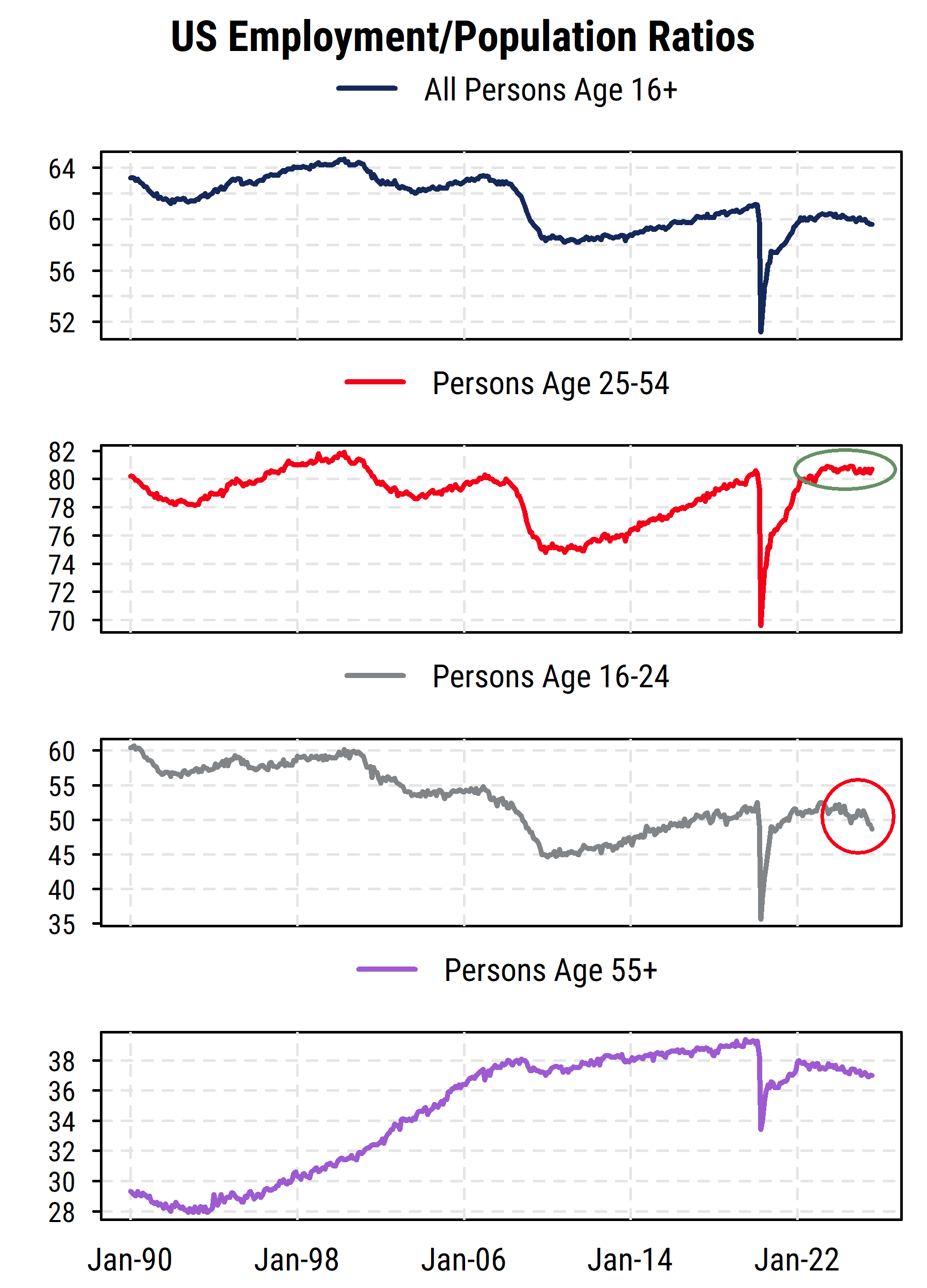

The employment/population ratio broken down by age allows us to adjust for demographic shifts in the population and see where the strength and weakness is. We can see that while the employment rate for “prime age” workers (25-54 years old) has held steady at solid readings so far, for young people (16-24) it has been falling while older people have also seen a reduction in employment rates. The “fringes” of the labor market (younger and older) are clearly fraying while the “core” is holding so far as companies reduce new hiring but refrain from widespread layoffs.

Source: Mill Street Research, Bureau of Labor Statistics

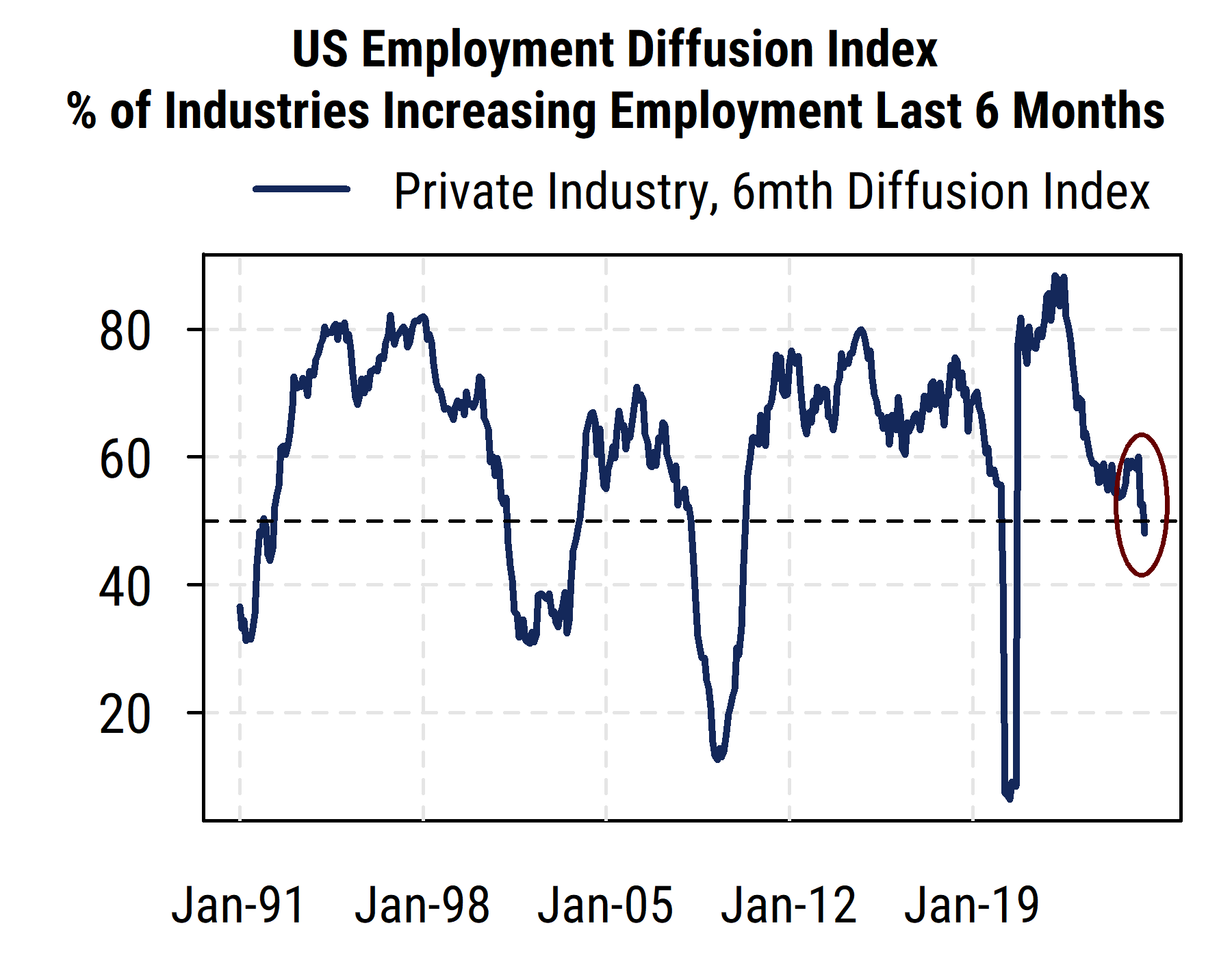

And when we look at the proportion of the 250 industries tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, we see that only 48% increased employment in the last six months. That is the lowest such rate outside of the short COVID-driven readings since the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis in 2010. It is unusual to see such low readings outside of recessionary (or immediate post-recessionary) environments, but it is harder to interpret right now given the volatility in the economic data caused by policy chaos.

Source: Mill Street Research, Bureau of Labor Statistics

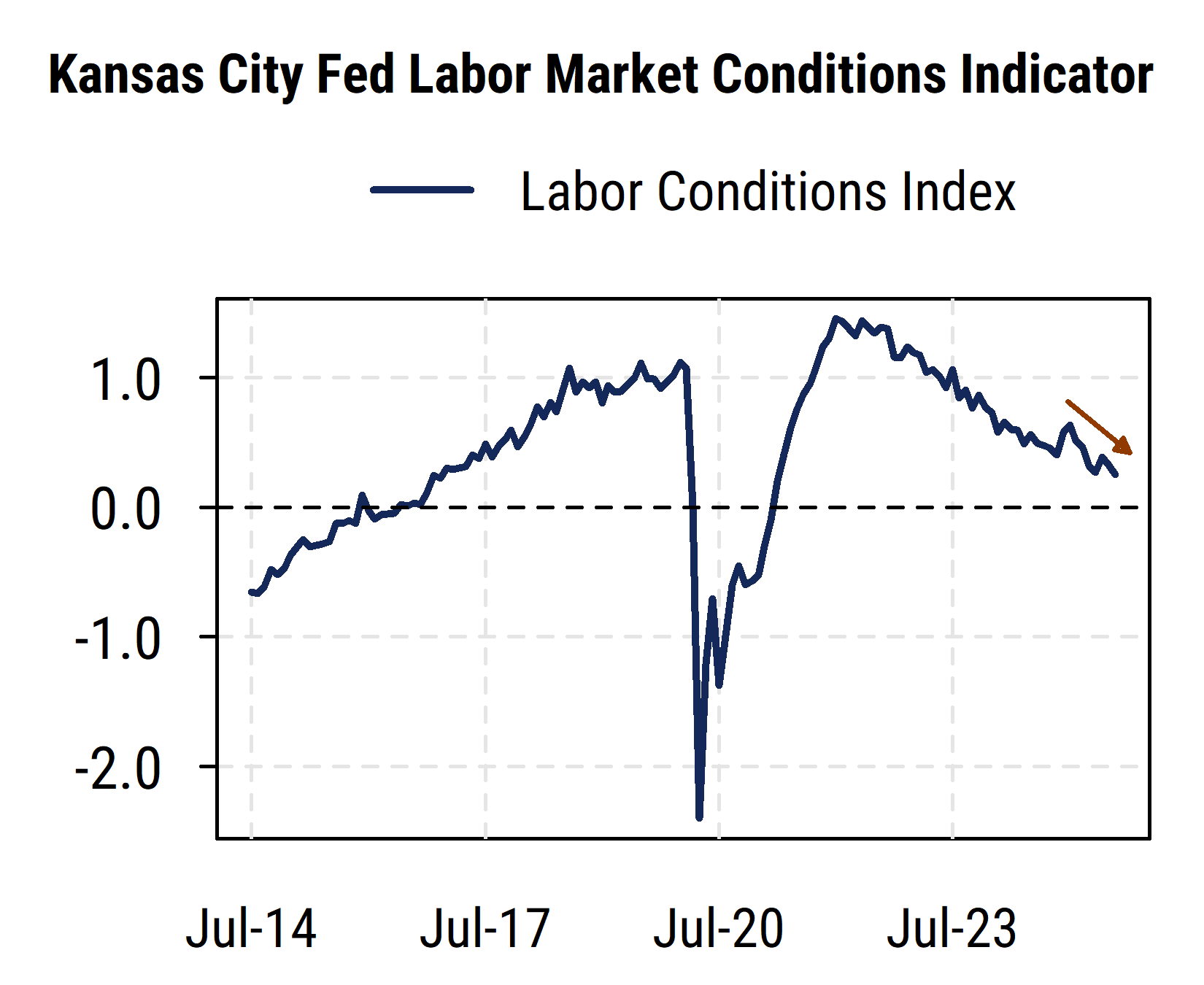

And finally, the Kansas City Fed produces a national labor market conditions index that summarizes 24 labor market indicators to construct an index that is centered around zero, which represents the long-run average. So readings above zero indicate that labor conditions are stronger than the long-run average (lower unemployment, etc.), while readings below zero indicate below-average labor conditions.

The indicator has been trending lower from the big post-COVID-stimulus jump, but is now quickly approaching the zero line that would increase concerns about the labor side of the Fed’s equation. Readings below zero are typically associated with low or falling real (inflation-adjusted) policy rates.

Source: Mill Street Research, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City

So the Fed has been facing a stark dilemma this year: do they hold rates at current levels, which have been viewed as relatively tight (restrictive) to try to keep inflation under control amid tariff pressures, or do they cut rates in response to signs of weaker employment growth to try to prevent the underlying economy from weakening too much and assume tariff-related inflation is “transitory” (i.e, a mostly one-off tax-driven price change, not persistent inflation).

After months of sitting on the sidelines, the first answer came at the September 17th FOMC meeting, where the Fed voted to cut rates by 25 basis points (0.25%) for the first time this year. This is notable because other global central banks have continued to cut rates this year, leaving the Fed as the odd one out, in contrast to the Fed’s usual leadership on global rates — US rates are still higher than those of most other large economies. Fed officials including Chair Powell explicitly said earlier that the Fed would have cut rates earlier this year if not for Trump’s tariffs and other policy chaos that made monetary policy far more difficult.

Indeed, one of the key risks for investors is that the Fed misinterprets the volatile and confusing economic data and then makes misguided policy moves. If economic data this year has been heavily influenced by consumers and businesses trying to alter behavior to adapt to huge policy changes like tariffs, immigration, health care, etc., then it makes the usual economic modeling and extrapolation from current data even more difficult (i.e., people pulling forward purchases of tariffed items before the tariffs went into effect, companies pausing hiring and investment decisions, etc.). This is especially true if policy itself is volatile and can change on short notice. So the Fed could decide inflation is transitory but labor market weakness is a longer-term concern, but the opposite turns out to be true (labor market and spending rebound soon while inflation remains high). The Fed would then potentially lower rates too much now and then be forced to reverse course and raise them later.

If the data wasn’t difficult enough, now politics . . .

The other factor making the Fed’s job harder, and thus the market’s view of future Fed policy harder, is that for the first time at least since the Nixon administration a US president is actively and aggressively pressuring the Fed to lower rates sharply. And Trump is not only telling the Fed what he wants them to do, he is openly trying to fire and replace Fed board members with his hand-picked and poorly qualified cronies who will vote to cut rates regardless of the economic data. The first has been Stephen Miran, who just joined the Fed board after the unexpected departure of Adriana Kugler to fill out the last few months of her term, but shockingly is not resigning from his position as chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers. He was confirmed and seated just before the September 17th FOMC meeting and was the only dissenter to the 25bp rate cut decision, arguing for a larger rate cut and making clear he wants rates to be far lower than the rest of the FOMC. This is the first time in at least 90 years that a currently serving White House official is simultaneously on the Fed board.

In addition to the recent appointment of Miran, Trump has tried to fire Fed Governor Lisa Cook, despite long-standing rules saying that the President cannot unilaterally fire Fed governors except “for cause” based on actions while in office. Trump’s accusations that Cook committed mortgage fraud are flimsy at best (and hypocritical given several Cabinet members did similar things), and would have occurred before she was in office anyway. Nonetheless, the Supreme Court is set to rule soon as to whether Cook can be removed while Cook’s lawsuit challenging her removal continues. Besides the Fed itself, investors are concerned that a ruling in favor of Trump would effectively end the Fed’s independence by allowing him to fire any Fed official at will and replace them with politically-motivated appointees who would almost certainly push for much lower rates when not needed and stoke inflation pressures. Indeed, just last week, a group including every living former Fed chair and many former Treasury secretaries and chairs of the Council of Economic Advisers of both parties wrote an amicus brief strongly urging the Supreme Court not to allow Trump to be allowed to fire Fed governors at will. Getting such an ideologically diverse group of policy makers to agree on something like this is fairly remarkable.

And potentially more worrisome for investors given the influence of the Fed chair on rate policy, Trump has also made it clear that he is unhappy with Fed Chair Jay Powell, despite having originally appointed Powell himself in 2017 (Biden nominated him to a second term as Chair in 2022). Powell’s term runs until January 2026 and Trump is considering who the new Fed chair will be. If investors view the new chair as potentially soft on inflation and willing to bend to Trump’s push to lower rates aggressively without a solid economic reason, it could actually push long-term interest rates higher as the yield curve steepens. That is, investors worried about inflation caused by excessively loose policy would sell long-term bonds and drive long-term yields higher rather than lower. Higher long-term yields could also have negative implications for stock prices.

Trilemma: Labor vs Inflation vs Politics

Amid heavy volatility and uncertainty in economic data and policy, the Fed’s official policy concerns boil down to the dilemma of which trend is more likely to be persistent versus transitory: labor market weakness or tariff-driven inflation pressure? The unofficial trilemma would include those factors plus whether the Fed can remain independent amid attempts to stack the board with Trump loyalists who will make monetary policy politically driven.

The September FOMC meeting indicated that for now, labor market concerns are somewhat outweighing inflation concerns, but it is still close. Investors seem to be ok with the status quo for now, though that is largely because the Big Tech/AI leadership in US stocks is largely independent of the trend in rates. That is, the growth assumptions supporting US stock prices are based largely on surging Technology demand rather than whether rates are a half a percentage point higher or lower (debt costs are not a key factor for earnings of US mega-cap Tech stocks). If the enthusiasm for Tech moderates, investors may increase their focus on monetary policy and the Fed’s unusual conflicting policy influences. An excessively loose Fed would raise structural policy concerns and could somewhat counterintuitively bring higher long-term rates.

Sam Burns, CFA

Chief Strategist