6 October 2022

Short-term movements in stocks, bonds, and currencies continue to be driven primarily by changes in investor perceptions about the Fed’s likely course of action over the next 6-12 months.

In response to client questions, the following are some comments and charts reviewing recent history and the current backdrop.

Looking back at history…

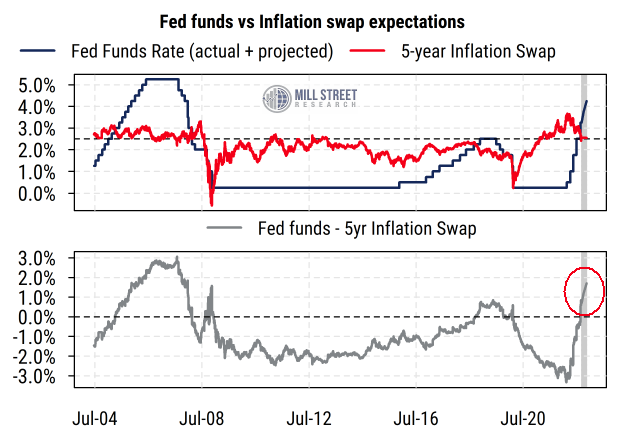

The first chart below is one we have shown before, which captures the current debate about Fed policy relative to market inflation expectations. It shows the historical and projected fed funds rate (based on futures prices through year-end 2022) alongside five-year inflation expectations drawn from the inflation swaps market (the most direct way of betting on future CPI inflation). The idea is to capture whether policy rates are high or low relative to expected future inflation, rather than compared to trailing inflation rates.

Source: Mill Street Research, Bloomberg

Source: Mill Street Research, Bloomberg

At least with the benefit of hindsight, the Fed was clearly far too tight relative to inflation expectations in the mid-2000s, and that eventually resulted in the Great Financial Crisis and severe recession. Of course, monetary policy was far from the only reason for the crisis and recession, as the banking and mortgage systems were horrendously overleveraged and under-regulated (something the Fed clearly should have paid more attention to). But the idea is that the Fed tried to use a very blunt economy-wide instrument (interest rates) to address a specific problem in banking/mortgages/financial markets, particularly when inflation expectations were not extreme.

After aggressively cutting rates to zero in 2008-09, it left them there (well below expected inflation) for about seven years, without any substantial upward inflation pressure – inflation expectations remained mostly stable and were often viewed as “too low”. The rapid removal of fiscal support after 2010 likely played a key role in the muted inflation pressures.

The Fed then began raising rates somewhat more cautiously in 2016, and got moderately tight on rates in 2018/early 2019 (along with aggressive balance sheet reduction) after the Trump tax cuts as rates went above expected inflation. That was shortly followed by an economic slowdown and a shortage of bank reserves (repo issues, etc.), which forced the Fed to quickly reverse course in mid-2019 (well before COVID) by buying bonds and cutting rates.

Then policy became extremely accommodative after COVID hit (rates cut back to zero and massive bond buying, including corporate bonds), but the COVID-induced supply constraints plus the fiscal response pushed inflation expectations up sharply, and they were above the Fed’s target by early 2021.

First mistake this cycle?

With fed funds still at zero while inflation expectations rose rapidly and hit new multi-year highs in 2021, the Fed’s first apparent mistake was being too slow to start normalizing rates, presumably due to uncertainty about the recovery from COVID. So it only began tightening this year after reported inflation had jumped and was already too high. Then Russia invaded Ukraine in February, causing another supply shock, mostly in commodity markets. And China locked down much of its economy in an attempt to contain the spread of COVID there, which has affected both supply and demand globally.

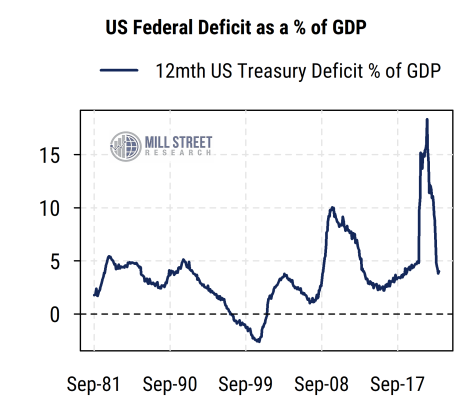

We have argued that US fiscal policy support (stimulus checks, etc.) were the biggest driver of the “excess demand” in 2020/21, but that fiscal support mostly ended in 2021 and has dropped off sharply since then. We can see this in macro terms in the US deficit/GDP ratio, which is now below pre-COVID levels (i.e., tighter fiscal policy), chart below. And supply (factories, transportation, etc.) in the economy has recovered alongside the reduced stimulus, which has pushed inflation expectations in the market down sharply.

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

Where are we right now – nearing a second mistake?

The 5-year inflation swap (like TIPS breakeven rates) is now back to about 2.5%, which is the Fed’s presumed target for the CPI. Many leading indicators of inflation (housing activity, commodity prices, shipping prices, ISM Prices Paid, non-auto retail inventories, etc.) are already pointing to much lower inflation, suggesting much of the Fed’s work may have already been done. But the reported CPI-type data that gets most of the headlines is well known to be lagging (and potentially mis-measured when prices are volatile) and will take time to come down.

So the Fed seems on the verge of following their mistake of being late to start tightening with another mistake of tightening too much and focusing on lagging (if more salient) data. The continued political pressure to “do something” aggressive about inflation is intense, if likely misguided.

Will something break?

Should the Fed act in line with current fed funds futures prices and have rates at 4.25% by year-end (i.e., raises rates another 100bps), rates will be the highest relative to 5-year inflation expectations since the mid-2000s (as shown in the first chart above).

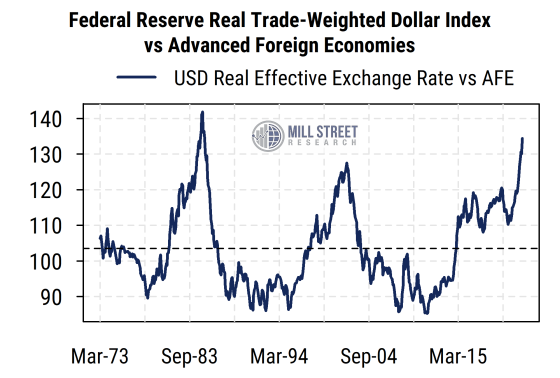

This has led to the growing concerns about a Fed-engineered recession and/or “something breaking” in the financial markets or banking system. The US banking system is in far better shape now than in 2008, but surging rates are still a concern for possibly overleveraged non-bank firms, and is having significant impacts on non-US economies and companies, particularly due to the extremely strong US dollar (chart below). Indeed, the Fed’s index of the inflation-adjusted (real) value of the US dollar relative to a basket of currencies of other advanced economies has surged to its highest level since the mid-1980s.

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

This is why markets are hyper-focused on the possibility of a “Fed pivot” that would suggest less future tightening now that rates are already above expected inflation, and likely to become excessively tight on current expectations.

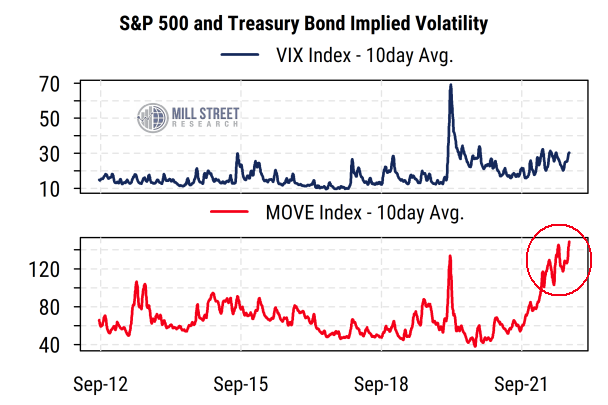

The extreme volatility in the bond market is one of the key indicators of this sensitivity, as we (and others) have noted, the ICE/BofA MOVE Index of Treasury bond volatility (analogous to the VIX for equities) has surged this year and is more than double its longer-term average. Equities also remain quite volatile, but not quite to the same relative degree as bonds and currencies recently.

Source: Mill Street Research, Bloomberg

Source: Mill Street Research, Bloomberg

The Fed of course knows this and is attempting to choose its statements carefully to avoid either provoking a market collapse, or a “premature” jump in risk appetite and easing of financial conditions.

To use a driving analogy, the Fed is essentially trying to slam the brakes on at high speed in a fog without running off the road (and arguably while looking at the rearview mirror). No wonder investor nerves are shaky.

In the short-run, market direction is likely to remain primarily driven by sentiment toward the Fed, and thus economic data has more impact than usual. Earnings reports for Q3 will begin soon and may have some impact if they come in far from expectations, but “macro” influences are likely to dominate “micro” (company-level) influences on stock prices for a while longer.