3 June 2021

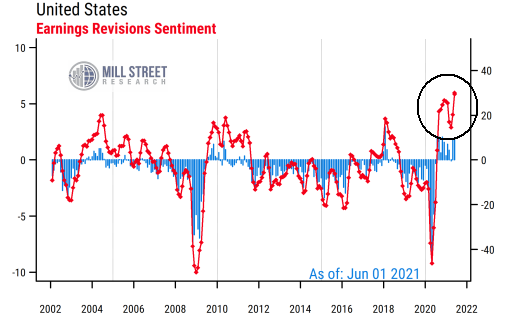

While we have commented on the strength in US earnings estimate revisions activity recently, the latest readings warrant additional comment. Our data now show a new record (20-year+) high in the net proportion of analysts raising earnings estimates for US companies. The latest reading exceeds the recent then-record high seen at the start of this year, as shown in the chart below.

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

One key takeaway is that “calling a top” in estimate activity can be as difficult as doing so for stock prices. The extreme readings seen in the November-January period certainly looked like they must represent a “top” in analyst sentiment and the only way to go from such peaks was down. And while there was a modest pullback in between earnings seasons, the latest surge has now eclipsed the earlier peak – what looked like a peak turned out not to be a peak. It may well be that estimate revisions activity is now more likely to pull back than accelerate further, and extremes by definition cannot be maintained for long periods. But a pullback from a peak that still maintains solidly positive levels is quite different from a severe decline.

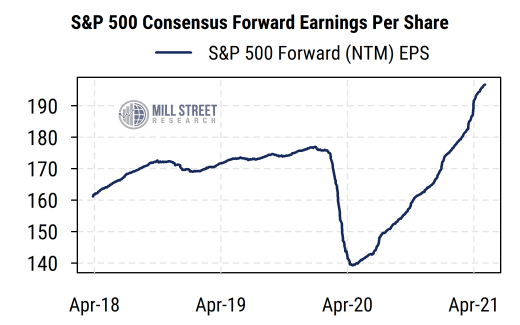

The chart below shows the path of consensus estimates for the S&P 500’s operating earnings per share over the subsequent 12 months. The aggregate index earnings forecast continues to rise at a rapid pace, and is nearing $200/share, now far above pre-COVID earnings levels.

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

We continue to face the natural questions: Why are earnings estimates still rising so much? Isn’t all the good news already included in analyst forecasts by now?

Analysts have consistently struggled to adapt quickly to major macroeconomic changes, which is somewhat understandable given their mandate to focus on individual company analysis. And the senior corporate executives who guide much of the analyst community’s activity may also find it difficult to forecast their own company’s fortunes when fiscal and monetary policy are shifting dramatically alongside a “force majeure” event like a global pandemic. This is not what is typically taught in business schools.

At a basic macro level, two things continue to stand out as the key drivers of the strength in corporate earnings: fiscal policy support and cheap capital costs (interest rates).

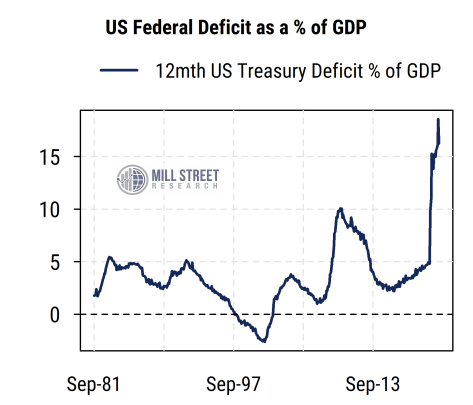

As the chart below shows, the size of the US federal deficit relative to GDP is still well above 15%, a level not seen in decades and near the levels seen in the mobilization for World War II. And the size of the fiscal stimulus is not the only extraordinary thing: the use of direct payments to consumers (stimulus checks, extra unemployment, etc.) is also of a historically unusual magnitude. That is, the current spending surge is not for overseas wars, but mostly given directly to US consumers, businesses, and state and local governments. Analysts and executives are like most of the rest of us in never having seen this level of fiscal activity before, and thus can perhaps be forgiven for having taken a conservative approach to their forecasts.

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

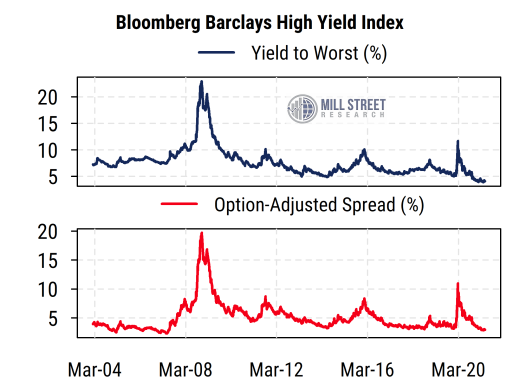

The other key element is that borrowing money is about as cheap as it has been in decades, even for the riskiest corporate borrowers (i.e., high yield, or “junk”, debt issuers). This is true both in absolute terms and relative to benchmark Treasury yields: low-rated (high yield) companies can borrow in the bond market for an average interest rate of only about 4%, and the 3% spread over comparable Treasury yields is also quite low by historical standards (i.e., a relatively modest additional return to account for possible defaults).

Source: Mill Street Research, Bloomberg

Source: Mill Street Research, Bloomberg

The combination of an economy getting this much fiscal support (driving demand higher) and the cost of borrowing remaining unusually low provides a very strong support for corporate earnings. Higher costs of inputs and wages due to supply constraints in some areas could squeeze profit margins at least temporarily, but the net effect has been very positive for most companies. Effects of this magnitude will not last forever, but also do not stop on a dime – economic momentum is likely to carry forward a while longer in our view.