Given the rebound in the Financials sector’s relative returns recently, and the broader increase in investor interest in Value after a long period of underperformance, it’s worth a look at some of the macro trends in the US banking sector to help identify trends that affect profitability. The data show both good news and bad news for the banking sector.

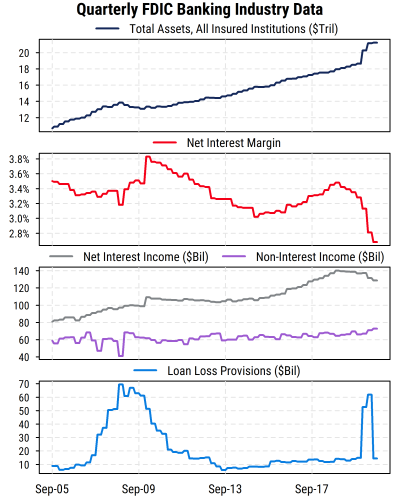

We first dig into the quarterly data on the US banking sector released by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), currently as of the end of Q3 (Sept. 30th, 2020), shown in the chart below. The top section shows the total assets of all FDIC-insured institutions in the US (about 5000 institutions), currently about $21 trillion.

The first key point here is good news for banks: assets have been growing steadily and showed a sharp jump this year as the Fed and Congress implemented massive stimulus programs, pushing lots of new money into the banking system. There is thus plenty of money that could be lent out and potentially produce income.

The next section in the chart shows the biggest piece of bad news: the net interest margin on bank lending has dropped dramatically to the lowest on record (data back to 1984). Record-low interest rates on Treasury benchmarks and narrow credit spreads (both driven by the Fed) have squeezed the spreads on bank lending, hurting profitability.

The third section of the chart shows the actual dollar level of two major categories of bank income: net interest income (the bigger category, grey line) and non-interest income (purple line). Net interest income is the difference between interest collected on loans and the amount paid on deposits or other bank borrowings that fund loans. Non-interest income reflects all forms of fees and gains (mortgage and lending fees, asset management, trading gains, etc.) that banks collect that are not part of the interest charged on loans.

We see that growing assets have helped the dollar value of interest income grow over time, but recently the drop in net interest margin has pushed interest income lower. Non-interest income, by contrast, has been steady and reached a new high recently. Banks are likely to rely more heavily on non-interest income going forward as long as net interest margins remain depressed.

At the same time, quarterly loan loss provisions jumped in the first two quarters of the year but in Q3 they quickly reverted back to pre-COVID levels as stimulus measures hit. The current COVID recession is not a banking system issue like the Great Financial Crisis in 2008-09, and banks are much stronger than they were in 2007, though there could be further credit losses if more stimulus is not forthcoming.

The good news/bad news is therefore that lending is much less profitable now, but growing assets and fees and trading gains have helped make up for it to some degree.

Beyond the question of the margins on lending, there is also the question of demand for loans, and the number of credit-worthy borrowers.

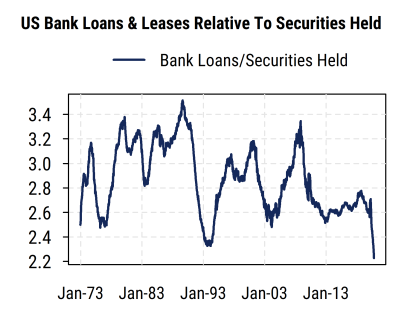

The chart below shows the ratio of assets held by US banks in the form of loans versus those held in securities. We see the dramatic shift in bank balance sheets toward holding securities (Treasury and mortgage-backed bonds, etc.) rather than loans, with the loans/securities ratio now at an all-time low (since 1973).

This is likely the result of higher assets but fewer credit-worthy borrowers to lend to, causing banks to park money in securities rather than making new loans. Credit standards have tightened sharply this year, which is not surprising under the circumstances, reducing the number of potential borrowers.

Owning securities rather than making loans is typically a damper on profitability for banks, since income from securities is typically lower than those on loans the banks originate themselves. This is likely one of the factors causing the net interest margin figures to decline.

Overall, banks have reasonably strong balance sheets and plenty of lending capacity, but face a reduced pool of potential borrowers. The macro environment and the Fed’s policies have sharply reduced the profitability of new loans, even if loan losses are not a major problem so far. These conditions are not likely to change near-term, given what the Fed has indicated about its likely future policy path. Fees and other gains could continue to grow along with total assets, but these factors may not be able to fully offset the lower profitability of traditional lending.