9 September 2021

A frequent question lately has been: are we currently in, or about to enter, a period of “stagflation” like the late 1960s and 1970s as a result of COVID and policy responses? Our short answer is no: while inflation may be elevated for a while, growth is currently strong, structural inflation pressures are low, and policy is better now than in the 1970s, making any sustained stagflation conditions unlikely. Below we offer some historical context and our current views.

The term “stagflation” originally arose in the 1960s-70s, and was a big deal then because mainstream economists thought it couldn’t happen: rising unemployment (economic “stagnation”) and higher inflation were not supposed to occur together, due to belief in the theory of the Phillips Curve, which says unemployment is inversely related to inflation, so they should not both go up at the same time.

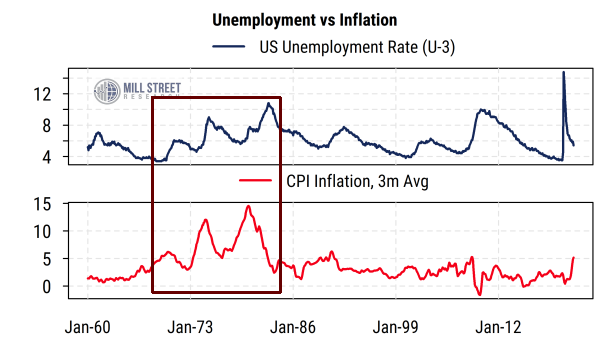

Now of course we know that inflation and unemployment are less correlated than people thought then, and that inflation can happen alongside weak growth. Large supply or demand shocks to the economy or major policy mistakes can cause both weak growth and higher inflation. The chart below plots the history of the US headline (U-3) unemployment rate and the headline CPI inflation rate since 1960. The red box highlights the stagflation period from the late 1960s through the early 1980s. So far, the current unemployment and inflation conditions do not resemble that earlier period.

Source: Mill Street Research, US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Source: Mill Street Research, US Bureau of Labor Statistics

THEN:

In the 1960s-70s in the US the major drivers of the stagflation were the “guns and butter” policies of high military spending on Vietnam and the Cold War (which tended to be “unproductive” spending economically, and took a lot of young men out of the domestic labor force for a while) along with expanded social programs. These initially included Medicare/Medicaid, the “War on Poverty”, etc., which were arguably good programs but increased federal spending significantly. Later, federal programs in the 1970s to stimulate the economy and also reduce inflation (e.g. “Whip Inflation Now!”) were put in place but were largely unsuccessful.

Also, in the 1960s and 70s, the Baby Boomer generation was having a major impact – there was a great deal of demographically-driven demand. That is, the population boom that started around 1946 and continued through 1964 was entering prime spending years and having children of their own in the late 1960s and 1970s.

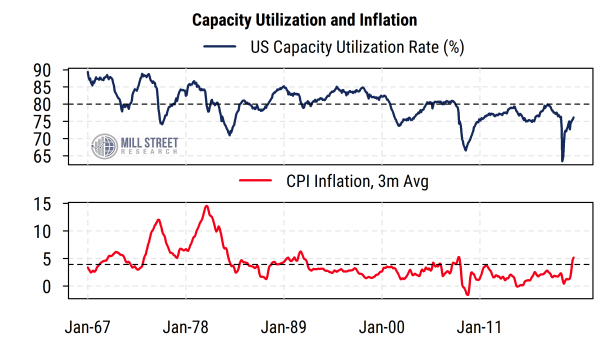

The result was an economy running much closer to its output capacity and thus the point at which companies would increase prices in response. The chart below shows the capacity utilization rate since 1967 along with the CPI inflation rate. We can see that in the late 1960s and 1970s, factories were running near capacity more often, which is a textbook condition for accelerating inflation. In recent decades capacity utilization has been much lower, and remains so today, a key reason for the low inflation rates we have seen.

Source: Mill Street Research, US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Federal Reserve

Source: Mill Street Research, US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Federal Reserve

This expansion of fiscal spending and Boomer-led consumer demand in the 1970s then crashed up against a massive supply shock in the form of OPEC’s oil embargo in 1973 (due to the Arab-Israeli War) and then a second oil shock in 1979 (mostly related to Iran). This pushed oil and all related fuel and transportation costs up dramatically: the retail price of gasoline in the US rose from 36 cents per gallon in 1972 to $1.31/gallon in 1981, a 264% increase in a decade. The importance of oil and transportation in the economy then caused prices for many other things to rise as well in response to the huge supply shock, and along with misguided government policies, very likely caused overall productivity growth to slow sharply.

The combination of weaker productivity, poor fiscal and monetary policy decisions, and the dramatic supply shocks in oil led to a mixture of slow economic growth, including recessions in 1969-70, 1973-75, and 1979-80, along with rising inflation (from 1% in the early 1960s to a peak of 14% in 1980 in the US).

NOW:

COVID-19 has been both a supply shock and a demand shock, and of course fully global, with demand shocks going in both directions in different industries. The demand shocks have not been evenly spread but focused in certain areas: lower demand for air travel, more demand for used cars. Less demand for restaurant meals, more demand for food at home and cleaning supplies. There are many such examples.

The supply shocks caused by COVID are in both labor (people who are sick, caring for the sick, afraid of getting sick, or can’t find childcare can’t work) and in many goods (semiconductors is a widely-cited example right now). Even in the health care sector, where one might expect higher demand, we have seen that demand for emergency health care is up, but demand for many other health care services is down due to people postponing elective surgeries, etc.

It is worth keeping in mind, however, that some of the supply issues we see today were already in place before COVID and caused by the Trump tariffs/trade war policies. For instance, imports of semiconductors from China were falling even before COVID hit due to US trade restrictions. And a wide variety of products were caught up in the multiple rounds of tariffs imposed on China and other countries (including Canada) on key inputs like steel, aluminum, etc. and everything made from them. This is often forgotten now, and those policies are still having an impact, but are likely to be curtailed under Biden.

Fiscal programs enacted in response to COVID have been historically large, and have given people more money to spend (temporarily) as well as limiting evictions, etc. A combination of more spending power and a reduced supply of things to buy has led to a rise in prices in a number of industries. At the same time, the OPEC cartel is still active (though less dominant than it once was) and has limited oil production to align with lower demand and keep oil prices near their preferred levels (currently in the mid-60-dollar per barrel range). Oil prices today are far from being the concern they were in the 1970s, as current prices are near the levels that were seen pre-COVID and are not excessive in a historical context.

The result is that there is clearly some evidence of higher inflation now, with the duration of the higher level of price gains still open for debate. However, the “stagnation” part of stagflation is not, so far, occurring. Employment is recovering rapidly, and real GDP is growing a strong pace, along with corporate earnings. One can argue of whether the economy is as strong as it should be, or how long the current high growth rate will last, but the economy is not currently “stagnating” by all the usual measures, even if economic data is no longer producing upside surprises relative to consensus expectations.

Some argue that once the heavy fiscal and monetary stimulus wears off, we will go back into recession (or very weak growth), and persistent supply chain problems (or ongoing COVID-related health impacts) will mean inflation will stay high, and thus we will then have true stagflation. This remains to be seen, but depends on policy decisions, the path of COVID/vaccinations, and on how fast the supply chains adapt, so it is hard to say it will definitely occur, or to what degree. Lower demand, if and when it occurs, will still reduce inflation pressure, all else equal. So low growth and inflation would likely only occur if supply limitations get materially worse.

Note that in these conditions, our view is that the quantitative easing (“QE”, or bond buying) programs by central banks are most likely not contributing significantly to inflation, and are not true “money printing” as some describe it (trading reserves for Treasury bonds among banks is not the same as a stimulus check from the Treasury). The Fed is primarily keeping interest rates across the yield curve low and banks well supplied with reserves, but these conditions alone do not cause inflation.

So we are much less concerned about the arguments saying “the Fed is printing money and causing inflation”. The money printing comes from the fiscal side (stimulus checks, etc.), and was certainly very large initially (appropriately so given the scale of the issues) but is already slowing down.

We can hope that the major central banks will realize that they should not tighten policy to address inflation caused by supply shocks, which so far they seem to (i.e., they appear to be avoiding a major monetary policy mistake). We can also hope the fiscal authorities will not cut back fiscal support too quickly, as they did in the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis (i.e., a fiscal policy mistake). And we certainly hope that the pace of global COVID vaccinations will improve and keep the health impacts under control. All of these are key sources of uncertainty.

Bottom line: inflation is up, but our view is that we are not in “stagflation” currently, as growth is sufficiently strong, and we do not expect sustained stagflationary conditions to develop in the near future given current conditions and policies.

Inflation caused by supply disruptions is harder to manage and to predict than inflation caused by excessive demand/money printing. Our view is that any “excessive demand/money printing” will ease by next year, and fiscal policy is much better now than in the 1970s or the post-GFC period, but full recovery in supply may be a bumpier path. We do not expect inflation to remain elevated on a structural basis (i.e,. we do not expect a repeat of the 1970s) but it could persist a little while longer. Once people can get back to work properly, there should be sufficient capacity to meet demand, but we won’t be able to see evidence of that until at least next year.

For investment purposes, our take is that stocks are likely a better place to be than bonds given current low yields and the fact that earnings go up with inflation. Real economic growth is still supportive for corporate profits. Stocks and bonds are arguably both expensive compared to historical averages, but stocks are not expensive relative to bonds in our view.