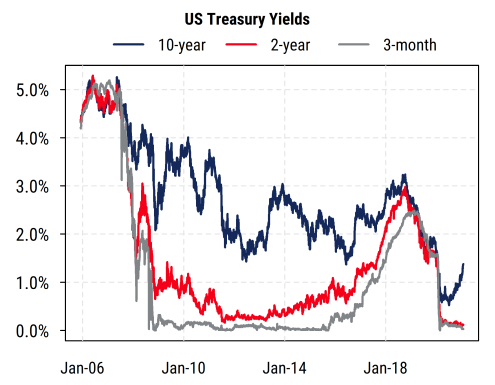

The bond market has clearly awoken from what appeared to be a low-volatility Fed-induced slumber for much of last year. Longer-term bond yields in the US and elsewhere have jumped to their highest levels since just before the COVID crisis hit markets early last year (blue line in first chart below). Even after this rise, though, the 10-year Treasury yield remains below even the low points of previous cycles.

Short-term rates (0 to 2 year), meanwhile, have remained anchored near zero due to the Fed’s continued indications that any policy rate hikes are still at least two years away.

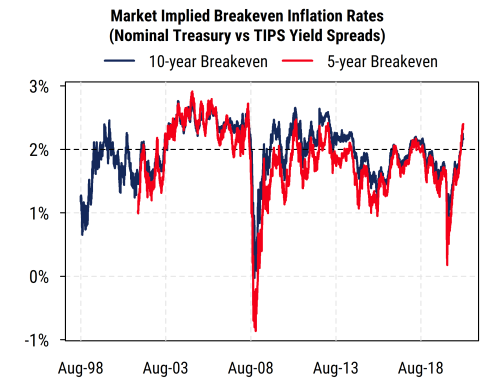

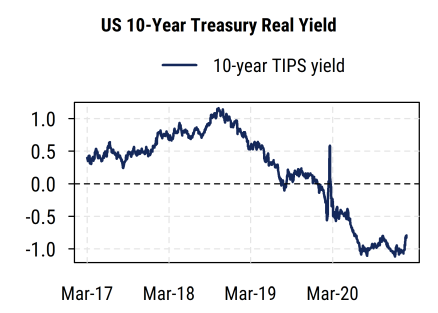

There are two main components to Treasury yields (which do not have default risk): real yields (yield after subtracting expected inflation) and inflation expectations. The first component to move was inflation expectations (first chart below), and more recently real yields (second chart below) have also risen notably. However, real yields remain solidly negative and much lower than they were before COVID-19 hit last year.

What have been the drivers of the recent move higher in long-term bond yields?

Some of the most prominent reasons include:

- Additional fiscal stimulus is expected soon, which will potentially boost inflation and growth, and also require the issuance of a large amount of new Treasury bonds.

- The economy’s recovery from COVID-related weakness is continuing thanks to ongoing vaccinations, which will combine with stimulus to push growth much higher than average this year.

- Sharply higher prices for oil and other key commodities (copper, lumber, etc.) are raising concerns about inflation already in the pipeline, with further demand potentially driving prices even higher.

- Selling or hedging activity by investors who trade leveraged positions in bonds, and/or own mortgage-backed securities that now appear riskier. Rising mortgage rates typically reduce pre-payments (due to less housing turnover) and refinancing of home mortgages, which increases the duration, and thus risk, of mortgage-backed bonds.

The jump in market-implied inflation expectations has been quite sharp, though something similar happened after the 2008 crisis period as well. The current inflation expectations reflected in 5-year and 10-year Treasuries (difference between nominal Treasury yields and inflation-protected TIPS yields) are now slightly above the Fed’s 2% inflation target. Indeed the 5-year implied inflation rate (breakeven rate) is at its highest level since 2013, and the 10-year rate touched its highest since 2014. Investors now appear to expect a rebound in inflation, which is likely not considered a problem by the Fed (given their stated inflation goals) as long as expectations do not become excessive. However, the Fed’s own buying of TIPS in the past year may itself have skewed the interpretation of “market expectations”: the Fed now owns well over 20% of the entire TIPS market, potentially influencing their prices (yields) more than usual.

For stock prices, a moderate amount of inflation is not necessarily a bad thing for corporate earnings, as long as it does not provoke Fed tightening. Since equities (via corporate profits) are partly hedged against inflation, real yields are often viewed as the more important rate. Thus the recent rebound in real bond yields has raised concerns about equities losing the tailwind they have had from falling real yields for more than two years. It has also provoked a shift in investor interest from Growth stocks that are attractive when economic growth and inflation are low toward Value (and other riskier) stocks that tend to do better when economic activity and inflation are accelerating.

With short-term yields still pinned near zero by the Fed, the yield curve has steepened sharply recently. This is notionally good for Value-oriented banks and other “spread lenders” (who borrow at short-term rates and lend at long-term rates), though many other factors can affect the profitability of lending, and higher rates can dampen loan demand.

And one of the biggest impacts of higher long-term yields is in fact on mortgage rates and thus the housing market. Housing has been an extremely hot area recently, as demand for single-family homes is very high and supply has been unusually low. The average 30-year mortgage rate recently hit an all-time low of about 2.8% but has now jumped back up to 3.14% in just the last two weeks (and will likely rise somewhat further near-term). While this is still very low by historical standards and may not hamper housing too much, at the margin it may cool demand, and any further increases would put additional pressure on housing demand.

Overall, a moderate rise in long-term yields with well-anchored short-term rates is not necessarily a major cause for concern for stocks, or the economy, in general. It does however mean potentially more rotation among sectors and styles within equities. It will also bring up concerns about whether or when the Fed will decide to alter its current policy trajectory in response, as too much of a rise in yields could cause economic dislocations that the Fed would prefer to avoid.