31 August 2022

China’s stock market (based on the MSCI China Index, which includes local Chinese listings and listings in Hong Kong) has lagged badly, whether compared to rest of the Emerging Market universe or to the developed market universe. The underperformance began in early 2021 and mostly continued since then, with a short rebound earlier this year that has since been reversed.

And the underperformance relative to developed markets (based on the MSCI World index) in US dollar terms (reflected in the US-listed ETFs that track the indices) has been quite dramatic. Since the interim peak in relative performance in mid-February 2021, the MSCI China ETF (MCHI) has returned -49%, while the MSCI World Index (ticker URTH) has returned -4%, a 45% underperformance in about 18 months.

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

China currently makes up about 30% of the broad MSCI Emerging Markets index, and that weight was larger last year before it underperformed the rest of EM. Over the same period (17 Feb 2021 to present), the MSCI Emerging Markets ex China ETF (EMXC) returned -17%, meaning China underperformed the rest of the EM universe by 32%. The overall MSCI Emerging Markets index (including China) returned -30% since mid-February last year, far below the -4% return for developed markets.

Why?

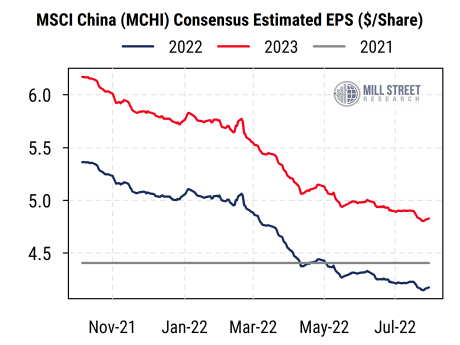

One reason for China’s underperformance has been that earnings estimates have fallen sharply, much more so than in developed markets. After starting this year expecting about 15% earnings growth for 2022, Factset data for the MSCI China index shows that analysts have slashed their earnings forecasts in aggregate for the index and now expect this year’s earnings to be about 5% below last year’s. The estimates for 2023 have also declined sharply, so much so that year-end 2023 estimates are now well below the earnings that had been expected for 2022 at the start of the year.

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

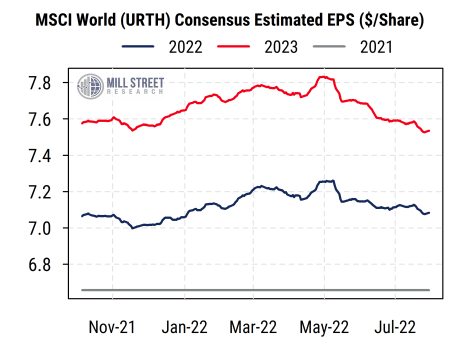

The pattern in earnings estimates for China look quite different from those for developed markets in aggregate. While earnings forecasts for developed markets (MSCI World Index) have declined recently, the forecasts for 2022 are little changed since the start of the year, and still call for just over 6% earnings growth in 2022, followed by a similar increase in 2023.

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

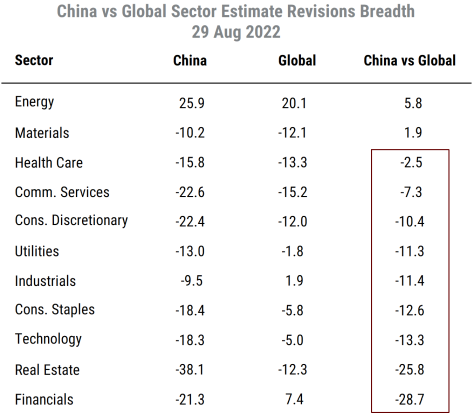

Is the earnings weakness in China tied to one or two particularly weak sectors? This question has come up more in the last year or two because the Chinese government has cracked down on certain large companies and certain industries that it perceives as a risk (or a threat), and earnings forecasts for those targeted companies have indeed been hit hard. However, we can aggregate the analyst behavior for our broad universe of about 700 China/Hong Kong-listed stocks to see what proportion of analysts are raising versus lowering earnings forecasts within each sector, with each stock weighted equally (i.e., not weighted based on market capitalization, which tilts toward the largest companies).

As shown in the table below, 10 of 11 sectors in China have negative revisions breadth (first column), meaning more analysts have been cutting estimates than raising estimates on average — only the Energy sector has positive revisions. However, this is not unusual right now, as earnings estimates globally are being cut, as reflected in our global sector revisions breadth figures (middle column) which show eight sectors with negative revisions. What we can see when comparing China with the global sector averages is that the readings in China are weaker than the corresponding global sector in nine of the 11 sectors. And in seven of the sectors, the gap is more than -10%, a significant difference.

So the relative weakness in Chinese estimate revisions is not narrowly focused in a few stocks or sectors, but is broad-based and reflective of overall relative economic weakness rather than idiosyncratic company/industry influences.

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

So earnings estimates in China have been falling, and Chinese stocks have underperformed, raising the question: is the bad news priced in? That is, are Chinese stocks especially cheap now relative to expected earnings and thus potentially attractive as a value investment?

Based on our comparison of the forward (next-12-month) earnings yields for China versus developed markets (MSCI World), it does not appear that Chinese stocks are particularly cheap relative to their usual valuation range. Chinese stocks have long been given lower valuations (higher earnings yields) than developed market stocks, which of course makes sense given the higher risks to owning Chinese stocks. As shown in the chart below, over the last decade, the MSCI China index has had a forward earnings yield about 2.6% higher (dashed line) than the MSCI World index. In Price/Earnings ratio terms, this is equivalent to a 10-year average P/E ratio of 11.3 for China versus 16.1 for MSCI World.

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

But right now, the earnings yield differential is in fact somewhat below average at about 2.1%, meaning Chinese stocks are, if anything, trading at somewhat higher relative valuations than usual. While valuation is a complex topic and forward earnings yields are only one metric among many that could be used, this metric suggests that there is not an unusual level of bad news being priced into Chinese stocks relative to those in developed markets overall (i.e. both have gotten cheaper this year, but China has not become meaningfully cheaper on a relative basis). So in our view it is hard to make a strong “value case” for buying Chinese stocks right now.

Macro backdrop is very different, and very challenging, for China

China clearly faces a very different macro backdrop than the US, Europe, or even other emerging markets. COVID lockdowns are still a major issue in China, but much less so in other countries now. The lockdowns have had a major impact on activity levels, and it is unclear when they will be fully lifted.

China also faces major concerns about its real estate market and the levels of debt associated with it. Investors and analysts have raised worries about balance sheets of real estate companies, banks, and Chinese mortgage holders. While China may avoid a 2008-style financial meltdown, the scale of the debt/real estate issues will likely be a headwind to growth (and earnings) for some time.

Indeed, unlike the US or Europe, no one in China is concerned about “excessive growth” or inflation. Even with the jump in global energy prices, the latest reported consumer price index for China showed just 2.7% year-on-year inflation, far below readings in much of the rest of the world. And China is in fact cutting interest rates and taking other actions to stimulate their economy, in sharp contrast to much of the developed world. The yield on 10-year Chinese government bonds (2.6%) is now notably below that of the US or Canadian 10-year (~3.1%), and even further below Australia (3.6%) or South Korea (3.7%).

In our view, Chinese stocks will not look attractive until there are clear signs that the relative weakness in earnings estimates has abated, or at least until there are better indications that all of the bad news is likely priced in. And since China is the largest country weight in the overall emerging markets universe (by a considerable margin), it will be hard to make a strong case for emerging market stocks in aggregate until China looks better.