28 September 2022

The August CPI report released earlier this month was significantly worse than expected, and data since then has not changed the broader view of inflation for the Fed. Along with continued hawkish public commentary from Fed officials, this has driven a further rise in bond yields to new multi-decade highs, and cemented expectations for further aggressive rate hikes by the Fed.

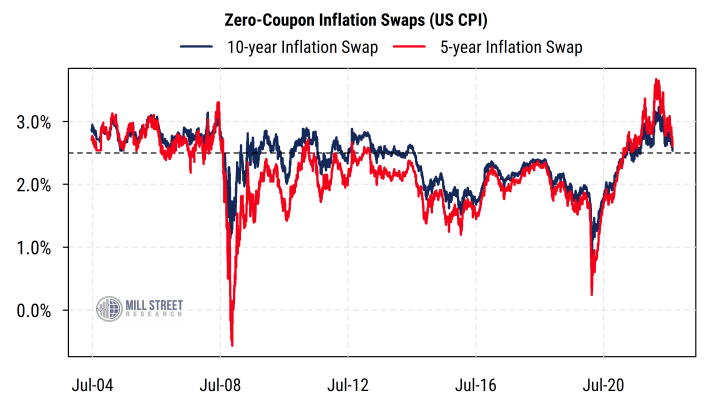

However, despite the “hot” CPI reports, the level of expected inflation in five-year inflation swaps (the most direct way to bet on future inflation) has fallen to its lowest level in a year, and was recently trading around 2.6% (chart below), close to the Fed’s presumed target of about 2.5% on the CPI (dashed line). A similar picture is seen in the 10-year inflation swaps.

Source: Mill Street Research, Bloomberg

Source: Mill Street Research, Bloomberg

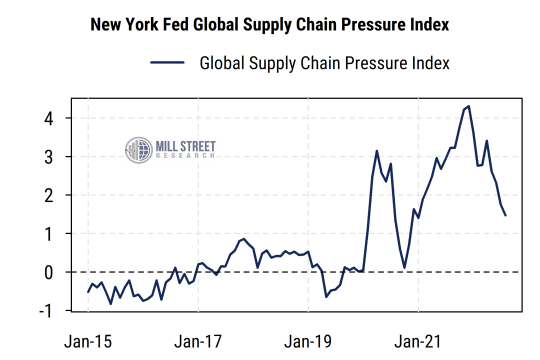

Thus markets clearly still expect inflation to slow sharply from its current high levels, and are likely watching more current or forward-looking indicators like commodity prices and supply chain conditions. Commodity prices have been falling recently, and the Fed’s measure of supply chain pressure (chart below) remains elevated versus history but has been falling steadily and rapidly from its peak for several months now as supply improves and demand eases.

Source: Mill Street Research, Bloomberg

Source: Mill Street Research, Bloomberg

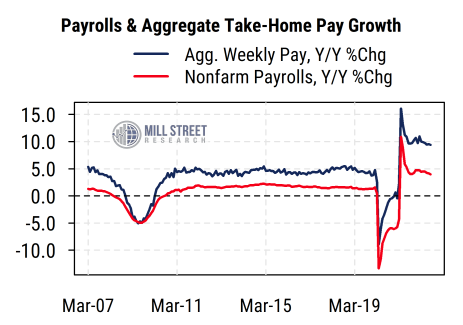

Aside from the reported inflation data themselves, the other key variable the Fed is watching is the labor market, and the growth of aggregate income. Payroll growth (people getting jobs) remains high, as does wage growth (jobs paying more). So the combination of the two means total aggregate (not per-person) incomes (aggregate weekly pay, which also incorporates weekly hours worked) are still rising at 9% year-on-year (chart below). While it naturally seems heartless to say, the Fed essentially feels that it needs to see fewer people getting jobs and raises in order for inflation to moderate. While this is true to an extent (i.e., if wage growth is higher than productivity growth), the issue is that labor market data tends to be a lagging (or at best coincident) indicator, and it ignores the supply side of the equation by focusing only on potential demand (though the Fed by itself can do little about creating more supply in the economy).

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

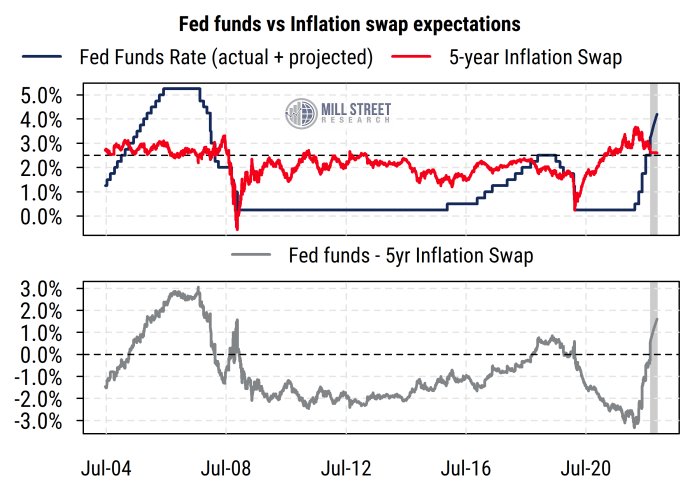

Until now, from a policy perspective the Fed has arguably been “tightening” policy rapidly but had not yet reached “tight” policy, which could be viewed as having policy rates meaningfully above expected future inflation rates (not trailing reported inflation). The chart below shows the fed funds rate actual level to present and the consensus expectations through year-end 2022 based on current futures prices (shaded area). It shows that the latest 75bp hike has pushed this measure of real policy rates decisively above zero.

If the Fed follows the market’s current expectations through year-end, and inflation expectations remain where they are, policy would reach the tightest levels since the mid-2000s by this measure. The impacts of tight policy next year (along with the sharp drop-off in US federal fiscal support) are likely the reason markets expect the Fed to have to reverse course later in 2023 as the economy slows more and supply returns, bringing inflation down with it.

Source: Mill Street Research, Bloomberg

Source: Mill Street Research, Bloomberg

There remains much uncertainty about how the Fed’s historically aggressive policy tightening will affect the economy, keeping in mind that it is also reducing its balance sheet by letting Treasury and mortgage backed bonds mature without replacement, known as QT or “quantitative tightening”. It has been such a long time since we have seen such policy constraint that comparisons are harder to draw, given that economic and demographic conditions even 15-20 years ago were materially different than they are now.

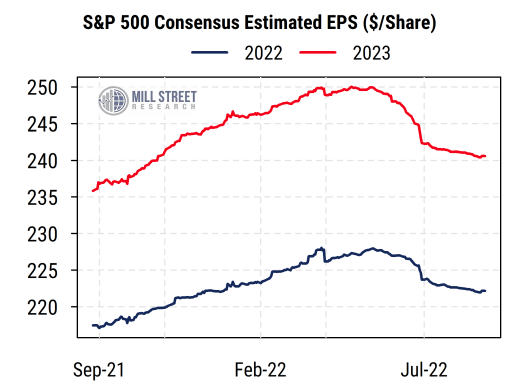

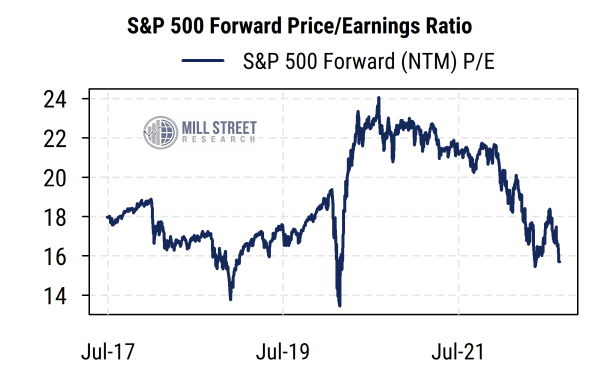

Equity analysts have responded by reducing earnings forecasts for 2022 and 2023 over the last several months, though they still expect about 8% year-on-year growth this year and next. While elevated inflation tends to flow through to top-line sales in aggregate for US companies, profit margins are potentially at risk, and a recession would bring down both inflation and real growth, hurting the top line as well.

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

Clearly some bad news is priced in, after sharp declines in both stock and bond prices this year, but the question of whether it is all priced in remains open. Investors are hanging on every report and Fed comment to gauge when the central bank will take its foot off the economic brake, and thus far are seeing mostly red tail lights ahead of them.

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset

Source: Mill Street Research, Factset