As we discussed in an earlier blog post (and in our client research), much depends on the path of monetary and fiscal policy, particularly the fiscal stimulus programs put in place in response to the COVID-19 crisis in March and April.

Back in March, hopes were high that by the end of July, the trends in COVID-19 would look better and there would be less need for such aggressive fiscal support. Sadly, that has not been the case, and the markets have clearly come to expect a new fiscal package to maintain support for the still shaky US economy. The concern is that a “fiscal cliff”, i.e., a sudden drop-off in government support before the economy has regained self-sustaining momentum, will lead to a renewed bout of heavy economic weakness.

Unfortunately for the millions of unemployed people who have been relying on a combination of state and federal benefits to get by, the fiscal cliff has already begun. The US Congress has allowed much of the fiscal support provided in the initial rounds of stimulus legislation to expire (or has been used up) and has not yet agreed on what (if anything) will replace it.

One of the key supports for the unemployed has been the additional federal unemployment benefit of $600/week (Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation, FPUC) that was being added to the regular state unemployment benefits (which average less than $400/week). The Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program also made benefits available to those who would not normally be able to claim unemployment (self-employed, gig workers, those caring for a family member, etc.). There were also provisions that provided federal funding for extended unemployment benefits to those who would have exhausted the normal duration of benefits (often 26 weeks) to a total of 52 weeks.

The provision of the extra $600 expired on July 25th and has so far not been replaced (Trump’s recent memoranda on the topic notwithstanding), while other provisions will expire at the end of this year. Congress and the White House continue to debate whether to extend the federal unemployment support and at what level, among many other things. Until they come to an agreement and pass new legislation, the additional federal unemployment benefits will remain unavailable. And even after a bill is signed, state unemployment offices will need time to make changes to their (mostly old and creaky) systems before claimants can receive the benefits, potentially leaving an extended gap in benefits.

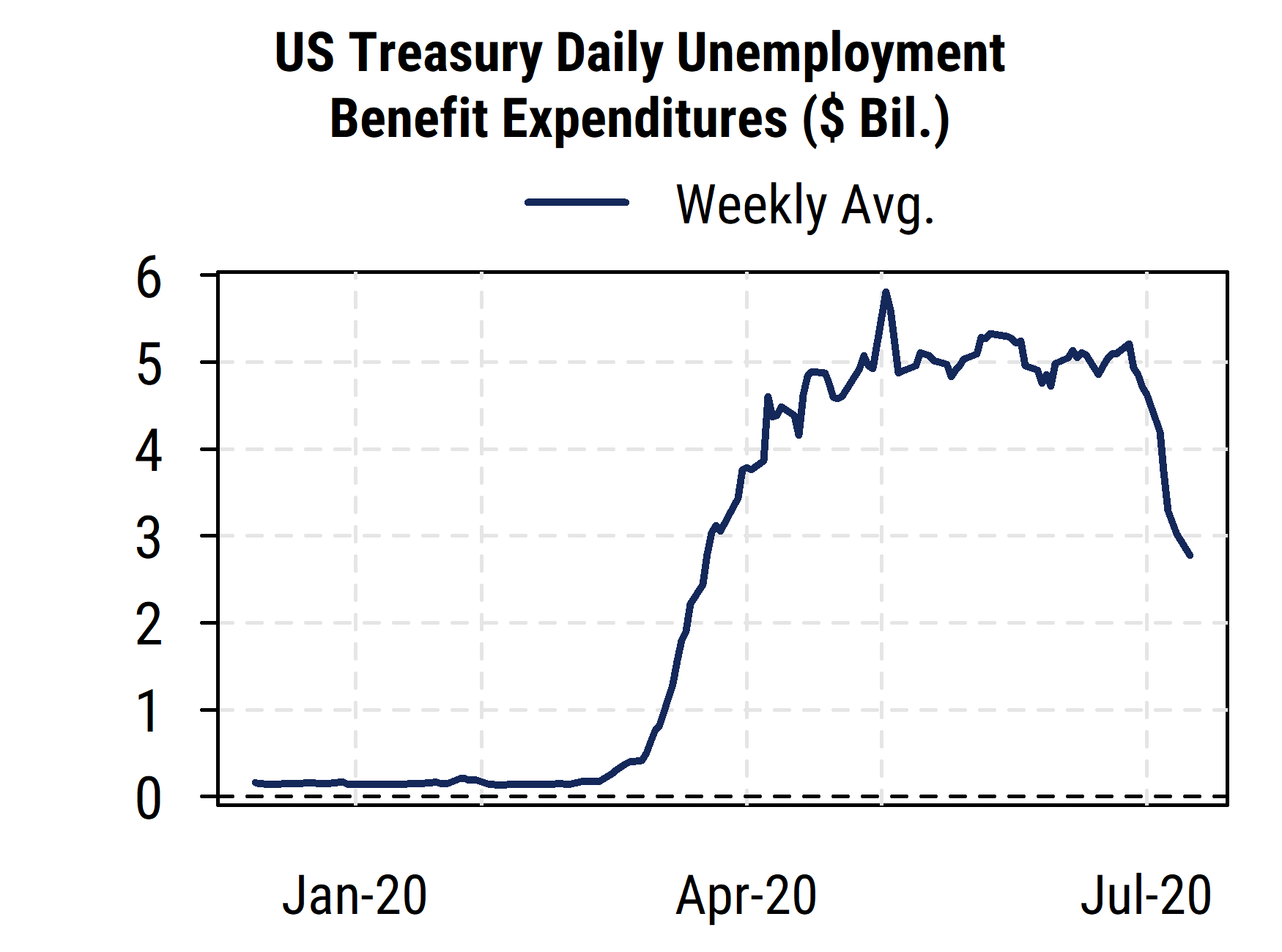

The chart above plots data released daily by the US Treasury, which shows the amount disbursed for all federal unemployment benefits. Prior to March of this year, the numbers were normally much smaller but surged to levels of about $5 billion per day, or $25 billion per week, from April to July. Since July 27th, the payments have begun to drop off sharply, with the weekly average already down below $3 billion/day and falling. A drop from the $5 billion/day rate to $2 billion or less (as it looks to be heading toward) equates to removing something like $15 billion per week (~$750 billion annualized), or more, of income support for unemployed people, who have a high average propensity to spend.

If the financial markets, earnings, and investor sentiment have been supported heavily by fiscal stimulus, and that stimulus (and political support for it) is now clearly fading even while COVID-19 continues to spread across the country, it raises questions as to whether the markets will have sufficient tailwinds to continue higher in the coming months.