*with apologies to Irwin M. Fletcher

Much has been made about the divergence between the path of the US (and global) economy and that of the stock and corporate bond markets. Even while economic and earnings growth is historically weak and remains under severe pressure from a rapidly spreading virus, major stock market indices have rallied and are at or near all-time highs. Market valuations based on forecasted earnings over the next 12 months have clearly risen sharply.

While the divergence between financial asset prices and the “real economy” as experienced by many Americans is striking, the reason is not hard to see: enormous levels of stimulus by both fiscal and monetary authorities.

Essentially, the US Congress has voted (in four separate pieces of legislation so far) to drastically increase deficit spending to support individuals and businesses as well as the costs of health care and virus abatement. The trailing 12-month US federal deficit has jumped to about $3 trillion, easily a new record in nominal terms and the largest deficit as a percentage of US GDP since World War II.

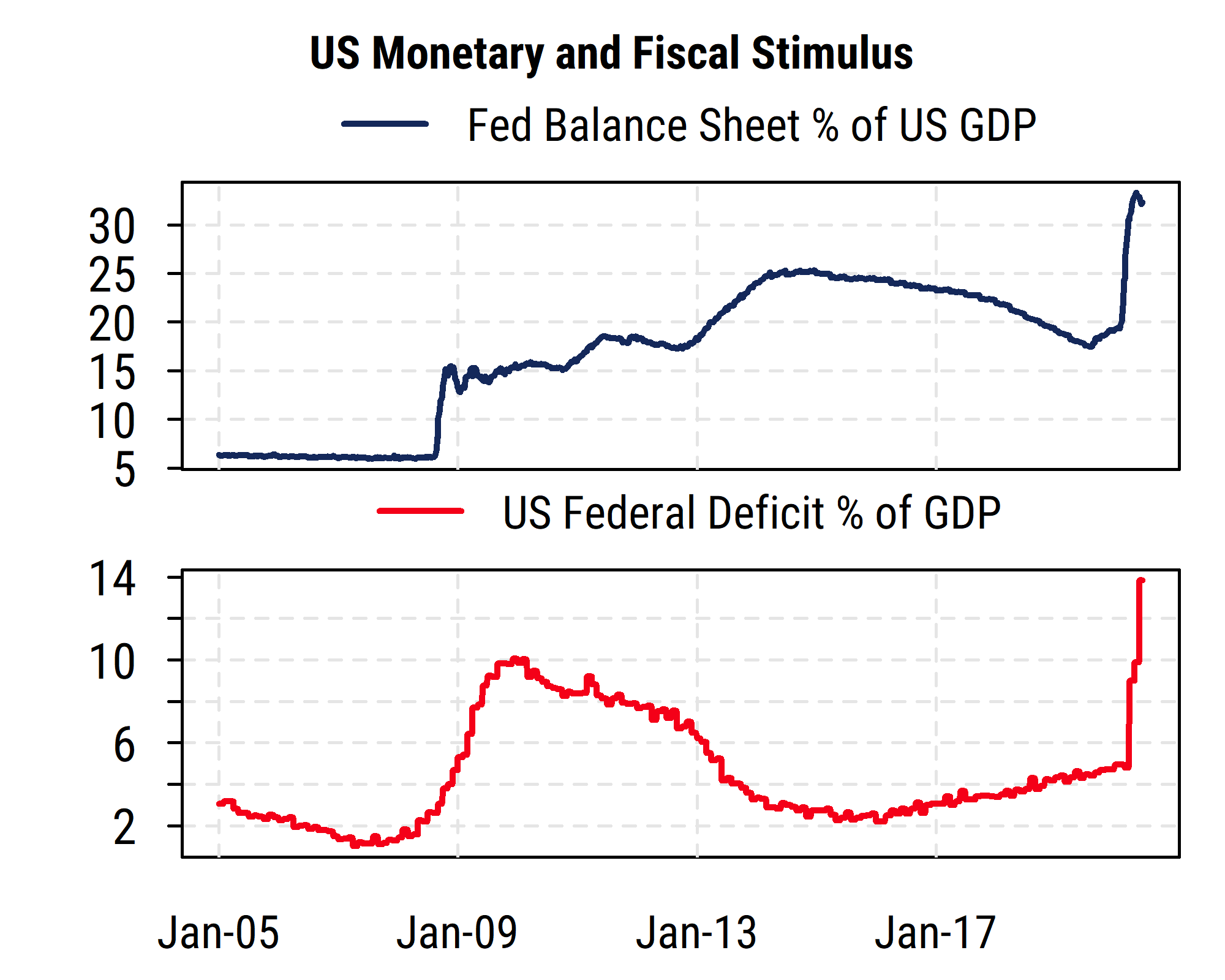

As shown in the bottom section of the chart below, the current 12-month deficit is now nearly 14% of nominal GDP, significantly more than the peak following the Great Financial Crisis, and up from the deficit levels of 4-5% of GDP in 2018-19, i.e,. adding roughly 10% of GDP to spending. This has helped fill a huge gap in personal incomes caused by lockdowns associated with COVID-19.

And crucially, at the same time, the Federal Reserve has also engaged in an unprecedented level of money creation (“quantitative easing”, or QE) to essentially monetize the increase in Treasury debt. After immediately cutting its fed funds policy target back to zero (0 – 0.25%), the Fed has expanded its balance sheet from around 20% of GDP before COVID-19 hit to over 30% of GDP currently, i.e., adding roughly 10% of GDP to the money supply. This is also far bigger than its balance sheet was after the three previous rounds of QE between 2008 and 2014.

While the Fed has a number of different programs in place to support financial markets and the economy, most of what it is doing is buying up Treasury bonds, mortgage backed securities, and more recently corporate bonds and bond ETFs. It does this with newly created money that can then circulate in the economy. A key effect is to essentially offset the absorption of money caused by the Treasury issuing huge amounts of new bonds, and has drastically expanded the US money supply. And by using newly-granted powers (under the recent CARES Act) to buy corporate debt (including some high-yield or “junk” debt), it has also compressed the credit spreads in the corporate bond market and made it cheaper for companies to borrow than it otherwise would be.

So an extreme oversimplification would be that the Treasury engaged in new spending of something on the order of 10% of GDP, and the Fed printed roughly a similar amount of new money to “pay” for it (a liquidity conversion of the Treasury bonds to cash), with some of that Treasury money being used to allow the Fed to take on corporate credit risk for the first time. That extra ~10% of the economy that has been conjured up by Congress and the Fed was meant to fill some of the hole left by the meteor that hit the global economy in the form of COVID-19.

The key question now is to what degree is additional stimulus needed, and will policy makers provide it to the appropriate degree? Current virus trends, structural economic damage COVID-19 has already caused, and rising debt levels suggest significant further stimulus will be required to bridge the gap until the economic effects of the virus have passed, though that remains a point of debate.

Investors who take the view that the policy response will be sufficient (or possibly even excessive) are likely those who are content to pay the same (or higher) prices for stocks and some bonds than they did in 2019, and assume that earnings will fully recover and stocks will be worth more in the future due to the lack of any competition from near-zero interest rates on safe debt (Fed policy rates are expected to remain near zero for several years at least).

Investors who worry that the policy response will falter may be more cautious, given the potential further weakness in corporate earnings that would also result. And one outcome in particular bears consideration: what if the fiscal response falters (due to Congress being unable to agree on sufficient stimulus legislation), but the Fed continues to intervene heavily in financial markets with quantitative easing and corporate credit spread compression (i.e., printing more money than can readily be spent)? Then financial assets, and unprofitable companies, might continue to hold up and inflation could eventually rise, even while the underlying economy weakens (with implications for income and wealth inequality).

That is arguably not far from what is happening now, as the Fed has adopted a “whatever it takes” approach and has few limits to the amount of monetary support it can provide. The question of further fiscal stimulus is the key question right now, as there reportedly remains a wide gap between Democrats and Republicans in Congress (and the White House) about the size and scope of any additional stimulus. With much of the original stimulus plans now fully utilized or expiring soon, there is a clear danger of a de facto sharp contraction in fiscal policy relative to the current extreme levels of support (the so-called “fiscal cliff”). Congress is scheduled to be in session for only a couple of weeks before going on August recess, and the key $600/week of extra unemployment benefits are due to expire on July 25th. The path of the economy and financial markets may depend on decisions made by Congress in the next few weeks.