1 December 2021

Fed Chair Jerome Powell testified before Congress on Tuesday alongside Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, and markets were listening. While many topics were discussed, the markets responded most to Powell’s indication that the Fed may speed up the recently announced tapering plan for the huge bond buying program (“QE”) that has been in place since March of last year. The initial plan for $15 billion/month reductions in bond buying would have brought the process to a close by June of next year, while a faster pace could do so by March. Markets also focused on Powell’s comment that the word “transitory” may no longer be applicable with regard to inflation: “it might be time to retire that word (‘transitory’) and try to explain more clearly what we mean.”

The suggestion is that the Fed is inclined to maintain or even accelerate its plans to reduce monetary stimulus and then start to tighten policy next year in response to inflation pressures, despite the recent concerns about the new Omicron strain of COVID-19. Of course, policy views could change rapidly if the new COVID variant(s) turn out to be worse than expected.

Stock prices fell on the news of a potentially faster withdrawal of stimulus, while the bond market’s reaction was mostly to flatten the yield curve. That is, interest rates on shorter-term Treasury notes (e.g. 2-5 year) were higher on the day while long-term yields (10-30 year) were actually lower, narrowing the spread between them substantially.

The key questions for markets with regard to potential Fed policy tightening come down to timing and magnitude. Tuesday’s comments suggested that the timing of tightening steps may be moved up somewhat (i.e., the Fed will reduce bond buying faster than previously expected, possibly raising rates somewhat earlier than anticipated), but so far the magnitude of the expected cumulative tightening has not changed much. This is fully consistent with the bond market’s response of raising short-term yields while keeping long-term yields stable or lower.

In other words, the markets seem to expect the Fed to get to the same place (level of future interest rates) as they did before, but potentially get there somewhat quicker than they thought.

What are markets expecting for potential future interest rate increases? We can look at futures prices on the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), the new-ish measure of secured overnight borrowing rates by banks and other institutions1. It is meant to replace (or be one replacement for) LIBOR as a measure of short-term borrowing rates among banks, but unlike LIBOR the SOFR rate is based on market transactions (not a survey) and reflects secured lending (“repos”, or short-term loans secured by Treasury bonds as collateral) rather than unsecured inter-bank borrowing. The SOFR rate thus does not have the same risk premium embedded in it as LIBOR can, and the SOFR futures have become more actively traded than the Fed funds futures contracts, especially for longer contract durations.

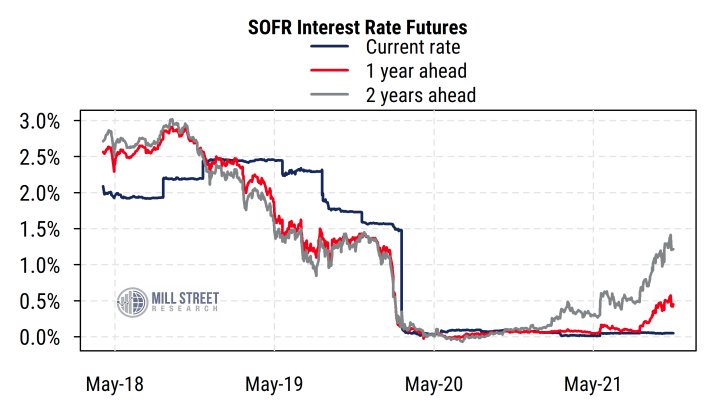

The current SOFR futures prices indicate that markets expect the Fed to raise rates by about 50 basis points (or two typical 25bp rate hikes) by this time next year, and then raise another 75 bps over the subsequent 12 months, bringing short-term rates to about 1.25% two years from now. The chart below shows the evolution of current and expected short-term rates since the futures began trading in May 2018. The rise in the grey line (representing the expected rate two years hence) began some time ago and has been stable in recent days. Markets have so far not raised their expectations of the Fed’s cumulative rate hikes in response to comments from Fed officials.

Source: Mill Street Research, Bloomberg

Source: Mill Street Research, Bloomberg

However, the other key point in the chart is that even two years from now, rates are not expected to be very high by historical standards. If rates in late 2023 are in fact only about 1.25-1.50%, that would be well below the rates of 2.5% seen prior to the last easing cycle (in 2018, when expectations were for 3% rates), which were themselves lower than the previous peak in rates. There is a reasonable chance that real short-term rates could still be negative (though less so than currently) two years from now if inflation stays above 1.25%, as many expect (as discussed in our previous post).

The bottom line is that while the Fed is expected to reduce its extraordinary stimulus (bond buying program) more quickly and start raising interest rates some time in the middle of next year, it is not expected to tighten very much relative to past cycles. With the US banking system still holding record levels of reserves, the tapering of bond buying will likely have only limited effects on rates or the economy. And if the rate hiking cycle ends up with rates only around 1.2-1.5% in 2-3 years, then monetary conditions will likely still be fairly accommodative by historical standards.

1 For more details on SOFR, see the Fed’s description here or Investopedia’s overview here