13 May 2021

According to the latest Consumer Price Index (CPI) report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, “the index for used cars and trucks rose 10.0 percent in April. This was the largest 1-month increase since the series began in 1953, and it accounted for over a third of the seasonally adjusted all items increase.”

Wow. That’s a big increase in used car prices, and a large influence for something that only makes up 2.7% of the overall CPI basket.

Based on questions we have heard from clients, we have compiled some data on used car sales and pricing as well as the financing of autos generally (new and used). This can help us gauge the relative impact of the auto market and whether the surge in used car prices is likely the result of demand or supply issues.

The chart below shows data since 2015 for various data series, as explained below. Source: Mill Street Research, Bloomberg

Source: Mill Street Research, Bloomberg

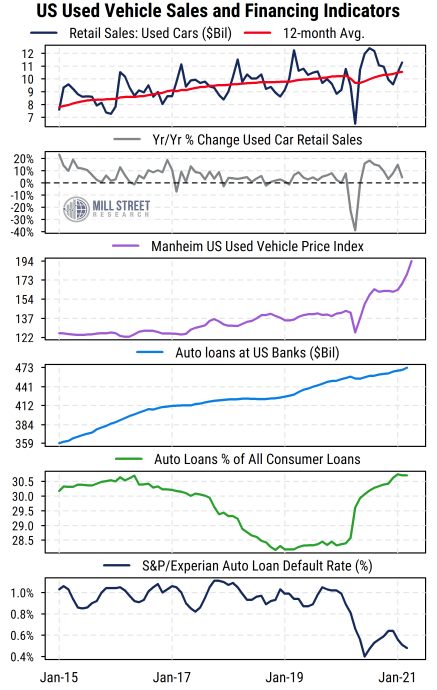

The top section shows the monthly retail sales data for used cars (in dollars, not number of cars), along with the 12-month average (since sales have seasonal fluctuations). Below that is the year-on-year growth rate of used car sales. In the third section is a widely followed index of used vehicle prices, the Manheim US Used Vehicle Index.

These three series tell us a few things. First, the surge in used car prices picked up by the CPI is also clearly evident in the Manheim index. That index (based on used car sales at wholesale auctions) is up 37% from its January 2020 (pre-COVID) level, and up 20% in the year-to-date alone (four months through April). Second, demand for used cars in the retail sales data has been fairly strong post-COVID, but not at the extreme level reflected in the pricing data. This combination of solid but unspectacular sales volume and skyrocketing prices suggests that limited supply is likely the key issue right now. Most likely supply has been limited by both COVID and reduced supply of new cars from auto makers, so that people who really want a car are paying up for them, and others are either priced out of the market or waiting for supply to improve.

The bottom three sections of the chart relate to auto financing, including both new and used cars. While overall bank lending growth has been weak recently, demand for auto loans has continued to rise, as shown in the fourth section. The fifth section shows auto loans at banks as a proportion of all consumer loans, and we see the big jump that started last year and has continued, now sitting at multi-year highs. So banks are clearly increasing their exposure to auto loans in both absolute and relative terms.

Is this a risk to banks if people do not pay their auto loans? While any loan can be a risk in theory, so far, the answer seems to be no. The bottom section shows the S&P/Experian auto loan default rate, which has tumbled to multi-year lows recently, currently running at roughly half the normal rate in the 2015-2019 period. The combination of stimulus and tighter lending standards by banks have thus far meant that borrowers are making their payments more reliably than before.

The bottom line is that demand for vehicles remains elevated as city-dwellers move to the suburbs and require cars, people have been uncomfortable using public transportation, and stimulus has made it easier for some buyers to afford a car. Supply has been constrained by people not selling their cars as usual during COVID, and the inability of auto makers to produce enough new cars to meet demand due to supply chain and labor issues. Banks have found an area of consumer lending that is growing (unlike, say, credit card debt) and are lending more, but so far the credit risk looks modest. Given the ongoing supply limitations in the auto industry, it seems likely these conditions could persist a while longer before demand and supply return to equilibrium.