The Mill Street blog has been quiet for a while, but will be more active now that the new website is up and running as we head into 2024, and updates will be emailed to those who request it.

In response to the recent market moves and headlines, I address one of the frequent questions from clients and the media:

After the latest FOMC meeting, the Fed’s tune seems to have changed. Will they really cut rates if the economy is still growing at a good pace, or even accelerating somewhat? Won’t more growth cause inflation to return?

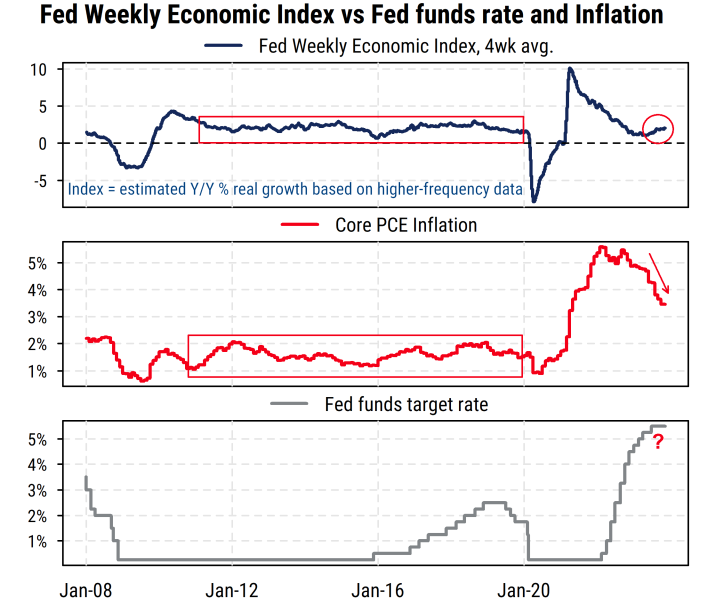

Real economic growth in the US is indeed holding up well at around 2% based on the Fed’s Weekly Economic Index1, and actually improving somewhat (in spite of the Fed’s aggressive monetary tightening), so based on the Fed’s history it may seem surprising that the Fed is now talking about rate cuts in 2024. But inflation is coming down rapidly nonetheless, bringing us to a potential “soft landing”, which would be a big “win” for policy makers as long as they can see it and not hit the economic brakes too hard.

Source: Factset, Bloomberg, Mill Street Research

My own view, which some but not all economics-types share, is that real economic growth being “too high” in major developed economies is almost never the true cause of inflation, and can in fact be deflationary in the intermediate- and longer-term if the growth is driven by investment (building factories, infrastructure, etc.) rather than consumption.

Excessive real growth is only the cause of inflation if the economy is truly running at its maximum capacity (i.e., all land, labor, and capital is fully utilized to its highest use). That has rarely been the case for the US, except during or just after war times (e.g. WWII).

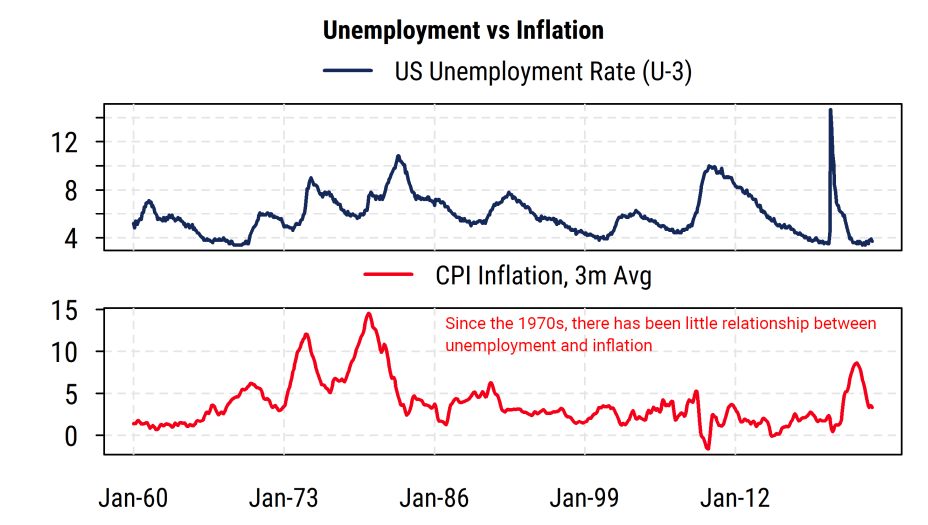

Fed may finally be seeing the weakness of the Phillips Curve

The main issue is the unwarranted continued prevalence of some version of the so-called Phillips Curve2. The Phillips Curve is an economic theory that basically assumes that there is an inherent trade-off between inflation and employment: when unemployment gets “too low”, inflation goes up, so if inflation is high, then higher unemployment is necessary to bring it down. It was first published in a 1958 paper by A.W. Phillips (using UK data from 1861 to 1957) and the theory was popular in the 1960s (the data seemed to support it in the 1950s and 60s), but data from the 1970s onward basically showed that the assumed relationship has not held up: there is little correlation between unemployment and inflation since the 1970s.

Source: Factset, Bloomberg, Mill Street Research

The Fed (and some other central banks) have, however, clung to the basic Phillips curve idea that “higher growth = higher inflation pressure” (with growth and employment assumed to move together). The implicit assumption is that the economy is closer to maximum capacity (at which point excess growth might cause inflation), when in fact it has rarely been near its true capacity (unless that capacity is constrained by a pandemic or war).

So whenever the economy shows signs of stronger growth and employment, the Fed tends to want to lean against it with tighter monetary policy. And markets have been taught by the Fed to respond the same way: higher growth means sell bonds and prepare for higher rates from the Fed (which may include selling stocks on the assumption the Fed will slow the economy and earnings).

The post-COVID period has more clearly shown that assumed relationship to be weak, if not broken entirely. Inflation jumped after COVID hit (and then the war in Ukraine) due to the mix of supply constraints and stimulus-driven demand, but once those “shocks” to the economy had passed (though COVID and the war in Ukraine are ongoing), inflation has since come back down while US employment has stayed quite strong (low unemployment and continued wage gains). That is, inflation has fallen without requiring higher unemployment, counter to what the Phillips Curve would suggest, and the Fed’s own assumptions.

Recent comments suggest minds may be changing

The most recent comments from Fed officials (including Chair Powell) suggest that at least some FOMC members are coming around to the idea that monetary policy does not have to tighten (or threaten to) every time there is evidence of economic growth, nor keep policy tight until the unemployment rate rises substantially. Treasury Secretary (and former Fed Chair) Janet Yellen has also made this case publicly.

Since current Fed policy rates of 5.25-5.50% on the fed funds target are well above reported and expected inflation now (and inflation is clearly falling), and the US yield curve remains heavily inverted (longer-term bond yields are below short-term bond yields, implying lower rates expected in the future), the Fed now suggests that it can, in fact, cut rates without waiting for slower economic growth as long as inflation continues to ease back to the ~2% target level. This “pivot” in the Fed’s thinking is potentially important, though it remains to be seen whether they will in fact follow through on the idea.

A soft landing has happened before, but it’s been a while . . .

In 1994 the Fed pursued a series of aggressive rate increases, much like 2022-23, due to stronger economic growth, and then cut rates in 1995 and early 1996 as inflation fell while the economy slowed but avoided recession. That is, a “soft landing” happened in 1995, and stocks did extremely well once the Fed took its foot off the brake. Investors today may be thinking about that episode from nearly 30 years ago as they have piled into stocks and bonds recently. It would certainly be a good thing for the economy and investors if the Fed focused less on weak theories like the Phillips Curve to allow the US economy to “run a little hotter” than it has in recent decades. Supportive fiscal policy (e.g., Infrastructure Act, CHIPS Act, Inflation Reduction Act) has been a huge help in providing investment-driven stimulus that has encouraged more private sector investment this year.

Too little growth is the risk, not too much

The bottom line in my view is that the bigger risk longer-term is too little economic growth, not too much, so policy makers (and also investors) should focus on that, and seem to have done so lately. Demographics, technology, and debt levels will tend to keep inflation pressures down in the absence of major supply shocks (pandemics, wars, OPEC, etc.). Fiscal and regulatory policy generally has much more impact on the economy than monetary policy, despite what many investors and policy makers think (or would prefer to think).

1 https://www.dallasfed.org/research/wei

2 https://www.stlouisfed.org/open-vault/2020/january/what-is-phillips-curve-why-flattened